New Westminster hosts unforgettable panel

By Mercedes Deutscher, News Editor

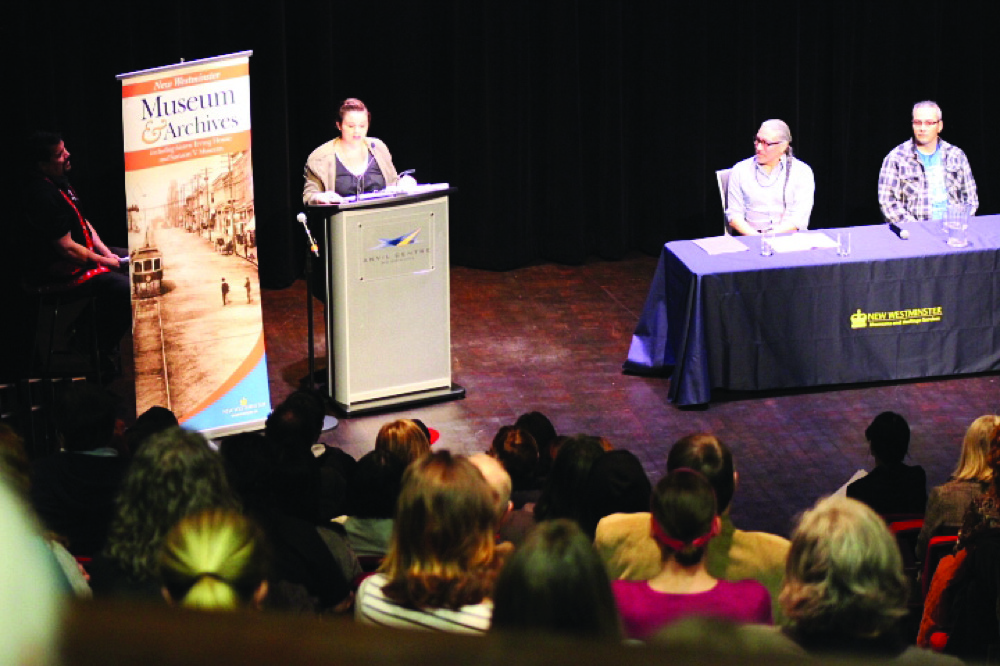

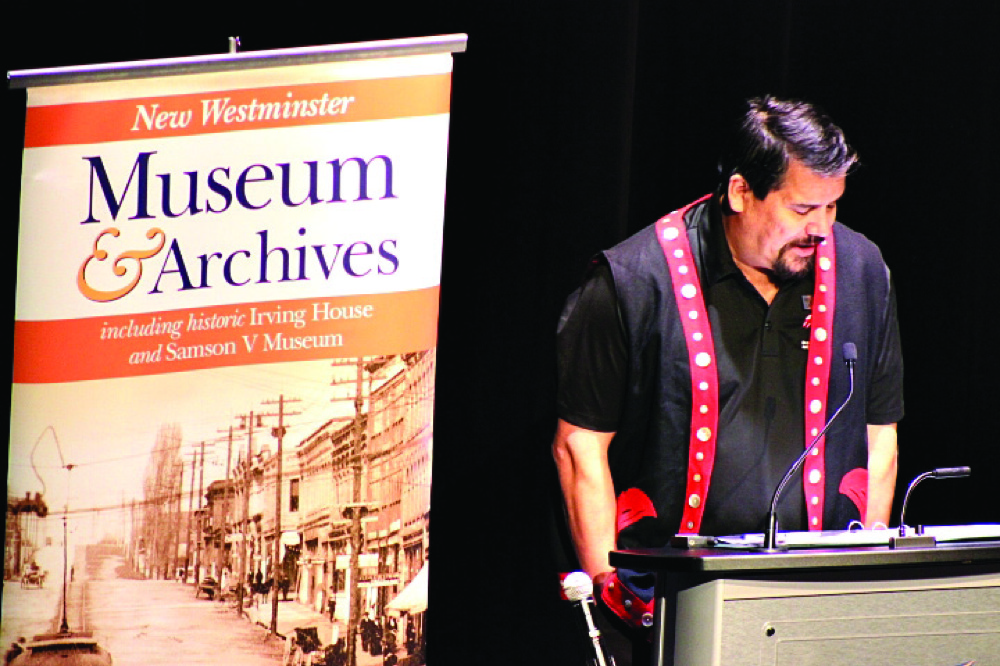

On January 19, New Westminster Museum and Archives hosted Community Stories of Truth and Reconciliation at the Anvil Centre. Along with the museum, the event was coordinated by the City of New Westminster, the Arts Council of New Westminster, QMUNITY, Northern Engagement, and Truth and Reconciliation Canada.

Dave Seaweed, Aboriginal Student Services Coordinator at Douglas College, mediated the discussion.

The event was attended by many notable members of the community, such as school board members, city councillors, New Westminster mayor Jonathan Cote, and New Westminster MLA Judy Darcy.

The panel was composed of four Indigenous speakers, who each gave a 10-minute presentation before the panel started answering questions from the audience.

Harlen Pruden, a nēhiyaw/First Nation Cree and managing editor at Two Spirit Journal, was the first panelist to make a presentation. Pruden discussed the fluctuating gender roles of Two Spirit indigenous persons. He detailed the roles in which these people served prior to European contact. After contact, Pruden described the treatment of Two Spirited people as derogatory. European settlers would often call the Two Spirit people “the berdache,” which attributed male members to be what was considered overly feminine.

Pruden described how residential schools had an effect on this culture by placing an imposition of gender roles that did not exist in the original nation. In addition to imposing set societal roles for its students, these residential schools kept families separated and broke family traditions.

“Family structure are key building blocks for healthy societies […] what else has been taken from us?”

The second panelist of the evening was Natasha Webb, who serves as president of the Douglas College Aboriginal Student Collective. Fitting to her role at the college, Webb told the story of how she helped establish a safe space for indigenous students at the college.

The collective was chartered in 2014, after some initial struggle to get official DSU club status. Webb feared that the collective would not take off due to lack of involvement, but after tabling, creating a social media presence, and visiting classroom, the collective gained enough members to become chartered. Since the collective was created, the Aboriginal Student Collective was able to attend the first Indigenous Students Conference in Victoria in November 2016.

Webb explained that healing can be found through education. Her keynote was opened with enthusiasm, as she detailed how her social work textbook had two chapters focusing on indigenous issues, with more coverage sprinkled throughout the textbook. Webb described it as a big step in increasing exposure for these issues.

“We all need to be represented so that we all may heal,” closed Webb.

Josh Dahling, who was adopted into the Squamish nation and works with Camp Kerry (which offers bereavement programs to children and families), was the third panelist of the evening, Dahling spoke about the long lasting damage in indigenous communities caused by colonization.

“I haven’t always been a saint,” conceded Dahling, who previously struggled with addiction and has relatives who continue to struggle. “It takes a community to heal.”

The fourth and final panelist was Cease Wyss, a Coast Salish woman who has been actively working at passing on art and culture both locally and internationally.

Wyss focused on discussing how people can reach personal reconciliation. She suggested that community and culture may be restored by focusing on decolonizing one’s self, mainly by connecting with children and youth, and then making an effort to practice cultural traditions. Through those activities, people may free their spirit, mind, and blood.

After the panelists had all had their chance to give presentations, the floor was opened up to the audience to ask questions.

Speaking to the role that municipalities play in reconciliation, Wyss advised the crowd to stop the celebration of colonization, alluding to Canada’s 150th anniversary this year, although she admitted that “We’re participating, whether we like it or not.”

Despite the seemingly widespread celebration, Wyss reminded the audience to not view indigenous reluctance to the celebration as negative, but to use it to gain a better understanding of indigenous issues.

Meanwhile, Pruden said that municipalities and government need to make relationships right again through policy and writing. He added that, since the government has historically spent money to implement colonization, it is only right that they use money today to help decolonize.

To address a teacher’s question of what they should teach children, Webb suggested that teachers use Aboriginal stories to educate children, as the colours and characters draw them into the culture.

Dahling added, “What you’re teaching isn’t as important as how you’re teaching.”

Yet perhaps the most harrowing discussion of the evening was in regards to the damaged family dynamics that have been left behind by the residential school system. A young woman from the audience described how her family had been negatively affected by the trauma experienced by a now-deceased member of her family.

Harlen described what his childhood was like with his own mother, who was also a residential school survivor, and offered a hug to the young woman. Harlen recounted how his mother would assault him and his siblings, while clarifying that much was a result of her own residential school experience.

“Our silence and our secrets keep us sick,” Harlen reflected.

Cease, whose mother had also been a residential school survivor, offered words of hope.

“Everytime she shared [her trauma], she shared more, and more, and more […] you being here is a step for healing.”