Still no word on the rent rebate promised by NDP government

By Katie Czenczek, News Editor

If you’re currently a tenant, you are not going to like this.

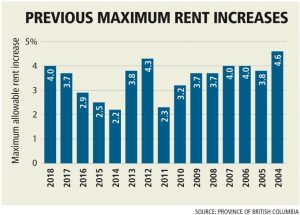

On September 8—a Friday, the weekly dumping day of political bad news—the BC government announced that next year’s allowable rent increase will be 4.5 percent, making this the highest increase since 2004. In order for this raise to come into effect, landlords must give their tenants a full three months’ notice prior to asking for more money.

According to the Ministry of Housing’s website, rent has gone up more than 30 percent in the last 10 years. With the current increase alone, it will be an 8.5 percent jump in two years.

The BC government set up a Rental Housing Task Force led by Spencer Chandra Herbert, MLA in the West End, in April of this year. The task force was in charge of consulting tenants, landlords, and tenancy advocacy centres all across the province to come up with a recommendation for renting legislation.

Andrew Sakamoto, the Executive Director of the Tenant Resource & Advisory Centre (TRAC), said in a phone interview with the Other Press that the change will be difficult for many tenants to swing.

“I think that it’s going to be a struggle for a lot of tenants, to be honest,” he said. “Rent increases are far outpacing wage increases for many tenants. Too many tenants across the province are paying an unhealthy amount of money on rent.”

The average cost for a two-bedroom home in Vancouver is $1,552 per month, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s 2017 report. If landlords choose to raise rent in 2019, the total rent would go up by $69.84, making the average monthly rent $1621.84.

TRAC was one of the advocacy groups consulted by the Task Force in early July. Sakamoto said that they recommended a temporary rent freeze, along with cutting the guaranteed two percent landlords get on top of inflation.

“Every year, landlords are allowed to raise rent a certain amount, but it’s not only based on inflation,” he said. “They also get a guaranteed two percent increase each year. What we proposed was first off, a temporary rent freeze for three years, to be followed by an amendment of the rent increase formula to eliminate that two percent that landlords get each year.”

The reason TRAC recommended a temporary rent freeze was to counteract the loophole landlords took advantage of in previous years. Previously, landlords could get around yearly caps by signing six-month contracts with vacate clauses, said Sakamoto.

“What [vacate clauses] allowed landlords to do is that after six months, they could kick out that tenant, bring someone new in, and jack up the rent to whatever they wanted,” he said. “Or, they could go to that existing tenant, give them the option to stay in the rental unit, but they would have to sign a new contact with new terms, with rent at any amount. That led to rentals all across the province to be artificially inflated. It was a way to circumvent the rent control in the Residential Tenancy Act.”

Although Sakamoto was disappointed in the announcement for 2019, he said that there’s still hope for legislation to address the rental housing crisis.

“We’re very pleased that the government mostly closed that loophole now, but we’re still feeling the effects of that. Despite all of the disappointment around this 4.5 rental increase among tenants, we’re still hopeful that this task force will lead to positive change in the area of tenancies. But in terms of protecting tenants in general—next year.”