Despite strong community opposition, shelter near David Lam campus will open in 2014

By Liam Britten, Contributor

Sandy Burpee considers himself a pretty lucky guy.

He had a good, stable upbringing as a youth in the Tri-Cities. A good career that he’s now retired from. And most importantly, he has always had someplace safe to call home.

But it’s an appreciation for the good things in his life that makes him so upset when he sees people in the Tri-City communities without adequate housing. He felt compelled to act, and so, for the past six years, he has been the chair of the Tri-Cities Homelessness Task Group. They are a leading organization in the area that has been advocating for more services to help the homeless.

“I’ve never worked in the field of housing or social services. But when you go downtown and see someone living on the street, it really strikes me as profoundly sad,” he said. “I feel called to do something.”

For years, the homelessness situation has been addressed by the Tri-City communities on a largely ad hoc basis, defined mostly by emergency shelters and the efforts of hard-working volunteers.

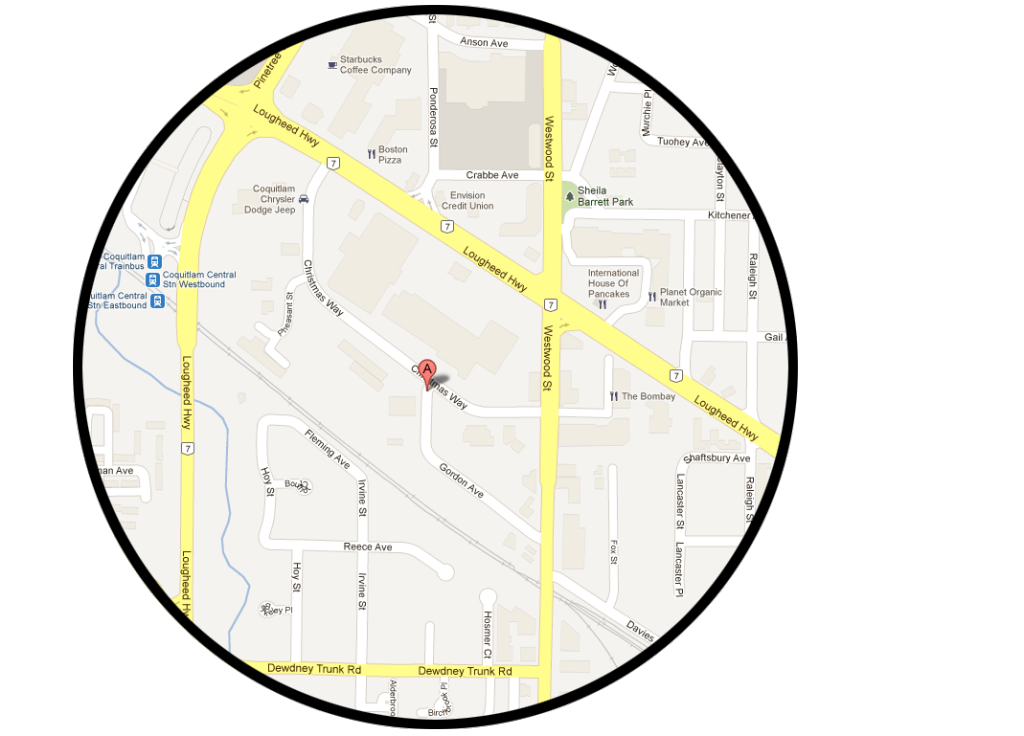

However, at 3030 Gordon Avenue in Coquitlam, about eight blocks from Douglas College’s David Lam Campus, a more enduring solution is soon to become a reality: a permanent shelter, with 30 long-term beds, 30 individual transition suites, and emergency beds has been approved by Coquitlam City Council, and is expected to become operational by fall of 2014.

For the homeless in this part of Metro Vancouver, opening day can’t come soon enough.

A wonderful day in the neighbourhood

When you think of the Tri-Cities, you probably don’t think that homelessness is that much of a problem. The heritage homes of Port Moody, the modern apartments of Port Coquitlam, and the hills lined with miniature mansions of Coquitlam seem far removed from the rundown, aging apartments of the Downtown Eastside.

That said, the area does have a homeless population, and they face special challenges unique to suburbia.

Many of them “sleep rough,” camping along the Coquitlam river and in other wooded areas. There they are threatened by the cold, the risk of accidental fires, and even assaults. Bylaw officers routinely uproot these camps, displacing the homeless once again.

There’s also the lack of services in this area in comparison to Vancouver, including hot meal programs, drop-in centres, and mental health services.

Compounding the problem are the politicians. The federal and provincial governments have been downloading responsibility onto the municipalities, Burpee said, and the city councils of Port Moody and Port Coquitlam have not made this issue a priority.

He said the one exception has been Coquitlam City Council, which he said has taken a key step in the right direction by providing land and funding for a shelter when other governments have not reciprocated their level of commitment.

“The city of Coquitlam has done some very important things to address homelessness, which has really made a large difference,” Burpee said . “The Task Group is profoundly grateful to them, because they stepped up and said, ‘We need to do something,’ when the provincial government has been very clear when they say they won’t support a project addressing homelessness.”

Their action is also fairly remarkable when you hear what voters opposed to the shelter had to say.

The pitchforks and torches crowd speaks up

On a cold November 29, 2011, Coquitlam City Council had one of their most heated meetings ever.

On the agenda was approving the 3030 Gordon shelter. There was no shortage of speakers representing the businesses and residents from the area.

Many were opposed to the shelter, citing fears of higher crime.

“They’ve got serious drug and alcohol addictions. How are they going to pay to support their habits? They’ll be breaking into my car again,” said resident Sandra MacDonald, quoted in a CBC News story.

RainCity Housing Society co-director Sean Spear has seen and heard from people like MacDonald for years. RainCity is a non-profit housing society that has worked with the homeless for 30 years, and has been chosen to design, build, and operate the new shelter. Whenever a new shelter is proposed, reactions like MacDonald’s are common.

“There was a lot of community concern, and people definitely had a lot of questions about this,” Spear said. “We’ve had some further community meetings … where we’ve met with the community, introducing ourselves to the community and the project. We’re still very interested in their concerns.”

Spear said that fears of crime in neighbourhoods with shelters are unfounded. He said that the same concerns are expressed again and again, only to not materialize.

“We just opened four shelters in Vancouver, running throughout the winter, and it’s a lot of the similar concerns: ‘Will there be drugs? Will there be disruption?’ All of that,” he said.

Burpee agrees that the fears are misplaced.

“Typically, the argument about social housing, wherever it’s proposed, is that it will increase crime, decrease property values, and it just doesn’t happen. It does not happen,” Burpee said. “It hasn’t happened with [temporary shelters], it hasn’t happened at Como Lake Gardens, the YWCA housing, and I’m quite confident it won’t happen at the permanent shelter.”

Spear said that by working with and listening to the residents who are concerned, his organization has turned many opponents into allies. Some of those foes-turned-friends even wrote letters of support for the Coquitlam shelter, testifying how problem-free RainCity’s shelters have been.

What can the shelter accomplish?

Although the project at 3030 Gordon is called a “permanent” shelter, the goal is not to make it a permanent residence. RainCity’s goal is to make the shelter a transition space, where shelter users can make connections to improve their connections with health professionals, career prospects, and life skills.

A particular focus will be on homeless women, who are often “invisible.” Homeless women often have roofs over their heads, but these situations are often dangerous and precarious.

The individual suites will be a safer environment for homeless women. They are to function as a long-term, but not lifelong living situation, from which they can hopefully find a permanent, independent home.

Spear said it was hard work getting the shelter, and RainCity’s operation of it, approved. He says he’s looking forward to making the shelter an integral part of the community.

But the real hard work—breaking the often years-long cycle of homelessness that many shelter users experience—will begin in fall next year.