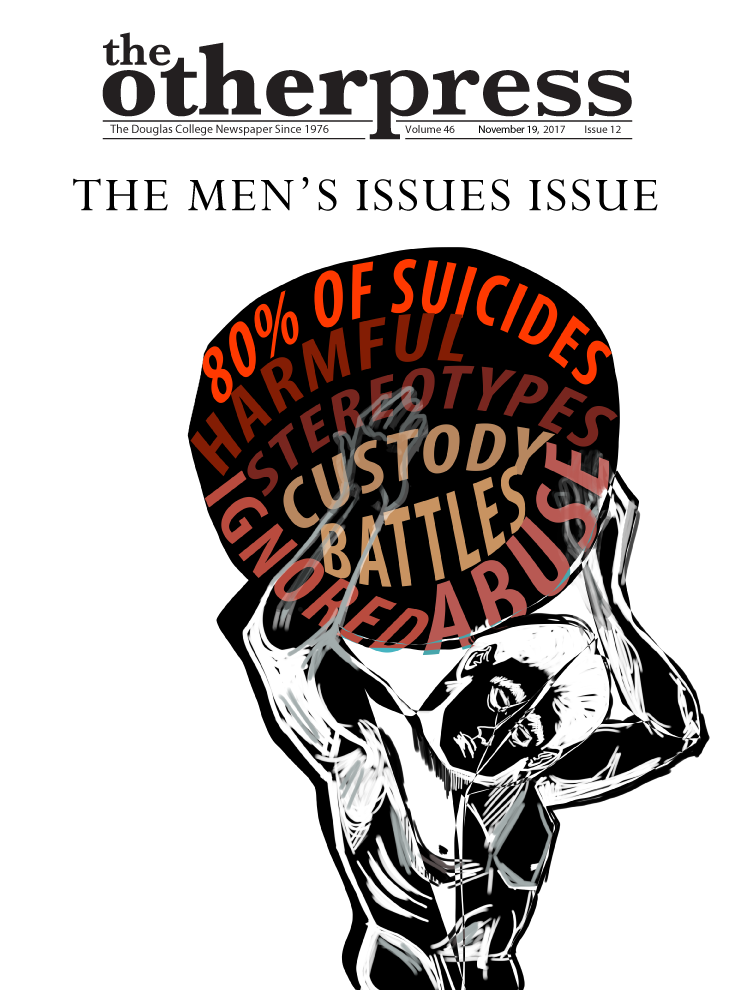

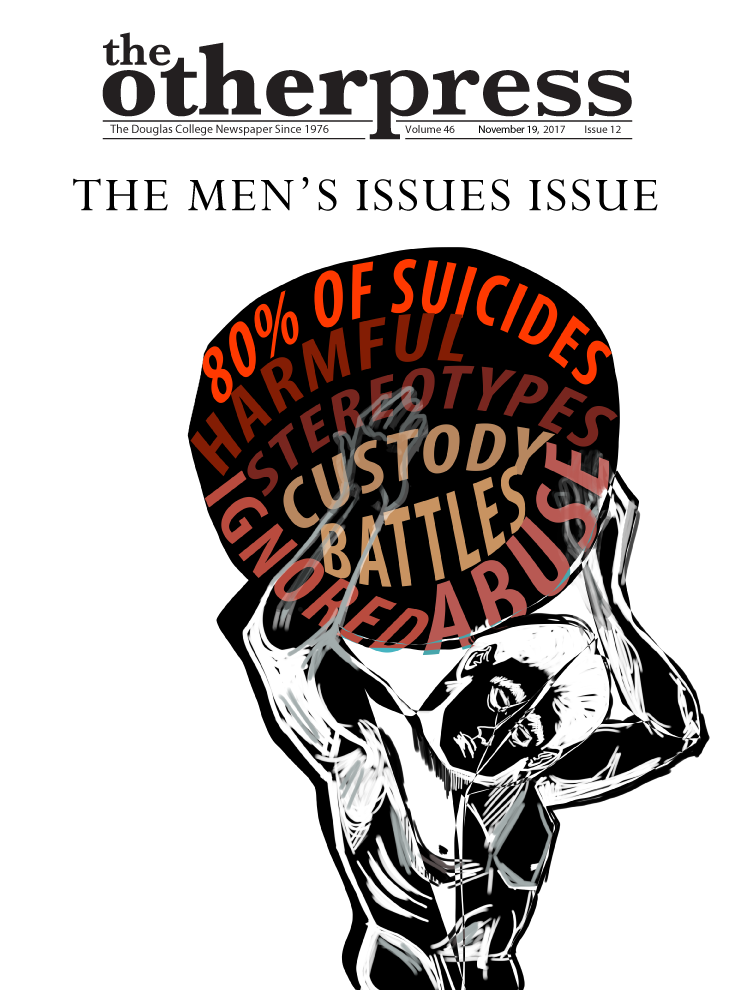

The epidemic of men’s issues that are largely ignored

By Jessica Berget, Editor-in-Chief and Janis McMath, Assistant Editor

November 19 is International Men’s Day and many question the need for a day dedicated to men. Some even argue that because men are in a position of power and privilege, they don’t deserve a day. The Other Press has compiled a few of men’s key issues—excluding false rape accusations, discrimination against men in female-dominated professions, workplace related deaths, and a lack of awareness of prostate cancer—that are important to address. These men’s issues, plus many more, highlight why International Men’s Day is important.

SUICIDE

While it is a known fact that women attempt suicide more often than men—about three to four times—the stats show that men’s attempts at suicide are much more fatal. 75 to 80 percent of deaths by suicide in Canada are made up by men. Men are more likely to die when committing suicide because their methods of suicide much more violent—usually by hanging or gunshot. According to Craig Martin, the Movember Foundation’s global director of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in Canada, eight men die by suicide every day, or 50 men per week. Psychologists recognize this epidemic and are investigating the potential causes, and several reasons surface when researching men’s depression and death. Men are less likely to reach out for help, says the American Psychological Association. Societal pressure tells men that showing their emotions is weak. A study by the British Journal of Developmental Psychology has shown that mothers talk more often about feelings with their daughters than their sons. This suppression of emotion this leads to men being ashamed and reluctant to search for help, and in turn, relying on unhealthy coping mechanisms.

“There tends to be more substance use and alcohol use among males, which may just reflect the distress they’re feeling—but we know it compounds the issue of suicide,” explains Harkavy-Friedman, the vice-president of research at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, in a BBC article. In fact, men are nearly twice as likely as women to form an alcohol dependence. Alcohol is a depressant, so drinking can worsen depression and make people more impulsive. Alcoholism is also a known risk factor for suicide.

Additionally, men’s occupations are another concern that could lead to feeling suicidal. A National Post article states that “Suicide in men may be linked to occupational stress. Men continue to make up the overwhelming proportion of people working in the most dangerous and dirty occupations […] Many of these jobs are subject to the whims of the seasonal and economic cycle, with periods of intense work followed by periods of unemployment. The very nature of these jobs can further expose workers to social isolation, separation from family, physical risk, injury and violence. This in turn can lead to higher rates of disability, substance use and post-traumatic stress disorder, all proven predictors of suicide.”

DOMESTIC AND SEXUAL ABUSE

Although women are often the priority in discussions about cases of domestic and sexual abuse, men are also often abused. In fact, according to the Canadian Centre for Male Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse, one in six men have been sexually assaulted in their lifetime. This number may even be underrepresented given the nature of how unreported sexual assault cases are. This is especially the case for men as the Association of Alberta Sexual Assault Services reports, stating that that male sexual abuse cases are even more unreported than women’s. This is because most men who go through sexual assault don’t report it or talk about it with people out of fear of being ridiculed, shamed, disbelieved, ignored, called weak, or have their sexuality questioned. Male survivors also fear being blamed for the attack because they were not manly or macho enough to stop or protect themselves from it. On a similar note, according to the Canadian Department of Justice, “The idea of masculinity includes physical strength, being in control, always wanting and being ready for sex, and being the perpetrator of such assaults, never the victim.”

It’s also a harmful stereotype that men can’t be raped because they are expected to be more sexual and therefore want sex more, so they “probably wanted it.” And if the perpetrator is an attractive, older woman, they should be happy to have the experience. There is also a lack of services and resources for male survivors of sexual assault.

Men are also woefully underestimated in domestic abuse cases. According to the Government of Canada, “Almost equal proportions of men and women (7 percent and 8 percent respectively) had been the victims of intimate partner physical and psychological abuse (18 percent and 19 percent respectively).” Furthermore, according to the Vancouver Sun, “26 per cent of the British Columbians who have been killed as a result of domestic violence have been men, according to a BC coroner’s report. The report said that in the decade ending in 2014, 113 BC women were killed in acts of intimate-partner violence and 40 men.”

The current narrative implies that men are the overwhelming majority of initiators of violence. As an article in the Toronto Sun points out, the Government of BC gives an outline of what law enforcement should do in cases of domestic abuse—in the Domestic Violence Response: A Community Framework for Maximizing Women’s Safety, it is stated that “Responses to domestic violence should acknowledge that domestic violence is a power-based crime in which, generally, the male in an intimate relationship exercises power and control over the female.” The document encourages this “gender lens” when approaching domestic abuse. But, as the stats show, and as Sarah Desmarais—a SFU PhD holder in forensic psychology who studies partner violence—agrees with, men are equally likely to suffer domestic abuse as women. It is true that women are more likely to suffer death from physical harm, and as she said in an article by CBC, “What we do seem to find is that even though the rates are similar, they are different in terms of their severity and also the likelihood that they’re going to inflict injury.” She goes on to clarify that, “[women are] usually smaller than their male partners and men are usually using more severe forms of violence.” Mentioned in the earlier Toronto Sun article, researchers’ study of the Statistics Canada population survey shows that men are just as likely to face physical violence from their female partners in domestic disputes, even if the outcome is different. It is certainly important to allocate special attention to the brutalization of women in this case of physical abuse, but it is vital to not allow these outcomes to skew perceptions on truth about the domestic abuse men face. There also needs to special attention allocated to empowering and supporting male victims of domestic abuse. On skewed perception, Desmarais says that the potential harms of the current view on male abuse “Are multiple. We could be looking at a lack of services available. […] There are much fewer services available, and also legal action that can be taken by a male that is being victimized,” she said.

CHILD CUSTODY

In the case of child custody battles, men are also disproportionately represented. According to the Canadian Department of Justice, mothers are more likely to receive exclusive custody of children during separation. In cases from 2006 to 2015, mothers got sole physical custody of their kids’ 61 percent of the time whereas men got it 10 percent of the time. In terms of legal custody, the numbers still show an inequality for men. This is because women are generally seen as the better caretakers. Furthermore, “The General Social Survey GSS (2014) reports that oftentimes the child lived primarily with their mother (70 percent), with 15 percent living primarily with their father.” According to a National Post article, “Many men report that the family justice system is institutionally sexist, casually entertaining false allegations while continuously ruling against them, regardless of actual circumstances.”

The reason the Other Press believes that these issues are so important is because of how little they are discussed and how widely they are invalidated. Case in point, in 2012 Simon Fraser University entertained the idea of creating a men’s centre, but it was quickly dismissed since “the men’s centre is everywhere else.” This is exactly why a day like International Men’s Day is so important and why we should all recognize its significance. If you’d like to contribute to solving men’s issues, the Movember Foundation is all about helping men.