The Universal Spirit

By Matthew Fraser, Opinions Editor

The Prophet is a book for solitude and uncertainty; in the strange and disconnected world of a pandemic, it is a soothing reassurance that transcends the confines of a single culture or faith.

Culture creates aides for the spirit, but too often those aids are contained within the culture and only serve the dominant group of the culture. Stories of wisdom and guidance are often trapped within the confines of religion and barred from secular sharing. One book that transcended the trap of secular animosity to religious teachings is The Prophet written by the late Lebanese poet, Khalil Gibran. Published in 1923, The Prophet garnered immediate acclaim and has never since sunken from wider cultural esteem. But in the early ’60s, new-age spiritualists and gurus brought Gibran’s work to the fore. The book begins with Al Mustafa waiting for a ship to come and return him to his people after 12 years on Orphalese. Al Mustafa spies from a hill a familiar mast on the horizon. From there, written with poetic elegance, The Prophet tells of the last hours that Al Mustafa spends with the people of Orphalese.

The Prophet is a book for solitude and uncertainty; in the strange and disconnected world of a pandemic, it is a soothing reassurance that transcends the confines of a single culture or faith. Blending the esoteric mists of eastern religion with the simplified air of a western tale, The Prophet manages to convey both quiet reassurance and the beauty of the mystic’s inner world. The villagers of the island gather around Al Mustafa to ask for his final guidance and final teachings before this journey home. This is a book that bares its heart through phrases both simple and enigmatic. When asked about time, Al Mustafa replies:“Of time you would make a stream upon whose bank you would sit and watch its flowing. Yet the timeless in you is aware of life’s timelessness, and knows that yesterday is but today’s memory and tomorrow is today’s dream.”

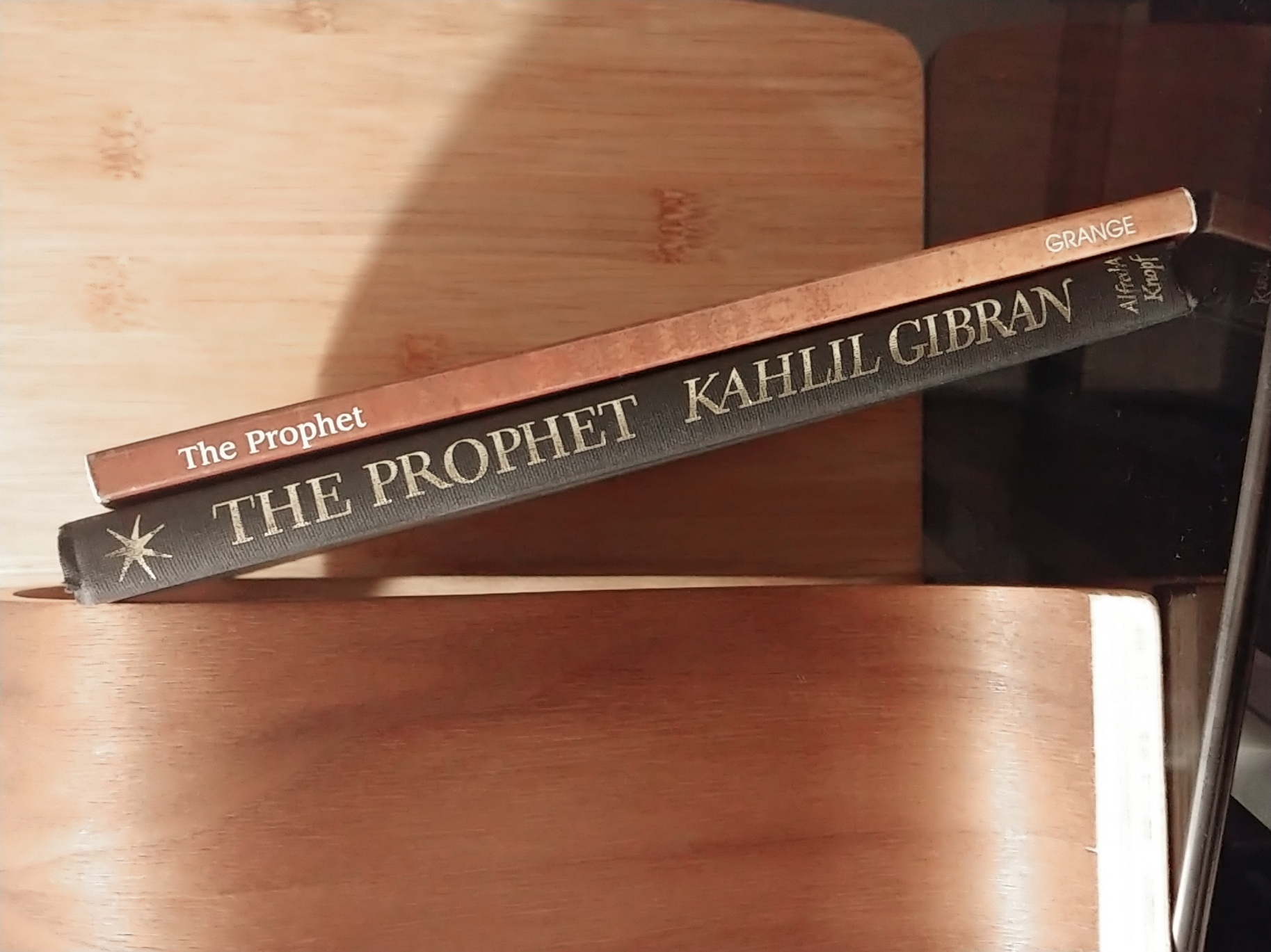

While The Prophet never strays from the spiritual airs of a religious text, its novella format allows it to exist as an otherworldly addition to any reader’s catalogue; it is living as fiction that travels with the reader through dreams and heartache alike. I recommend The Prophet so frequently that I have two copies, one for myself, printed in 1963—smelling of old age and long-forgotten book piles—and another printed in 2001 to lend to curious friends and as an aid in tumultuous times. The Prophet outlives Gibran not just for its simple elegance and timeless guidance but also for its non-denominal take on faith. Though the Bible may have Jesus and the Quran has immortalized Muhammed, Al Mustafa is unbound by land origins or a belief system. Al Mustafa’s world is only that of Orphalese and his words arebut asupport for the individual as they traverse the world around them.

Hostile or docile, painful or joyous, The Prophet takes the reader in hand on a solitary walk through the inner workings of a universal truth that never juxtaposes against faith but always reaffirms the eternal humanity of spiritual guidance. Leading not with the ironclad rule of organized religious fervour but with an introspective calm and clarity. The Prophet is best taken as an inspired spiritual aid; everlasting, singular, and without pretence, Gibran’s work is both made for poetic enjoyment and independent reflection. Its enigmatic guide is faceless yet sure, the wisdom encased between the books covers reinforces all without care for creed or origin.

Available for free online via the website of the same title, the simple, poetic and cleansing tome is the perfect salve for the dreary and unhappy days of pandemic isolation.