The art of the lift

By Adam Tatelman, Arts Editor

When people talk about bodybuilding, they usually mention larger-than-life figures like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Lou Ferrigno. Although these men were huge stars in their prime, almost solely responsible for the gym craze of the 1980s, their charismatic public personas did little to dispel the popular idea that bodybuilders are brainless beauties obsessed with “the pump.” But there is more to muscle than meets the eye.

Strength training has existed since humankind recognized the need for strength. Soldiers, hunters, and craftsmen have all relied upon the strength of their own bodies to protect and provide for their families, and only the strongest among them could survive the harsh conditions of the wild. For the same reason that packs of animals reject the weak and ill, so too do humans instinctively gravitate towards strength: it is the strong who lead, who accomplish, even if that strength is not necessarily physical.

Even the earliest cultures known to man had a healthy appreciation for the power of the human body. This is why ancient Greek art so often presents men with herculean physiques. Such statues are not necessarily meant to represent the men they were sculptured after, but rather to venerate their Olympian deeds. Socrates, for instance, was an upper-class philosopher. It is unlikely he was a muscular athlete. Perhaps sculptures idealize his body so as to to symbolize the power of his contribution to logical thought.

Strength of accomplishment has always been a popular focus of the arts, often shown as the result of physical strength. This is further reflected by the representation of men who abuse their strength. They are uniformly viewed as pathetic, spiteful, morally weak. Essentially, they are not true men. This is because, as Spider-Man is quick to remind us, “with great power comes great responsibility.”

So, strength can be the subject of art, and because of its historical utility, it is usually shown as a force for good. But can the act of bodybuilding be an art in itself? It is certainly a sport. There are athletes, admired for their incredible size and strength. There are competitions like Mr. Olympia, with massive crowds and bigger prizes. There are stars so bright that they cast a shadow over all future competitors.

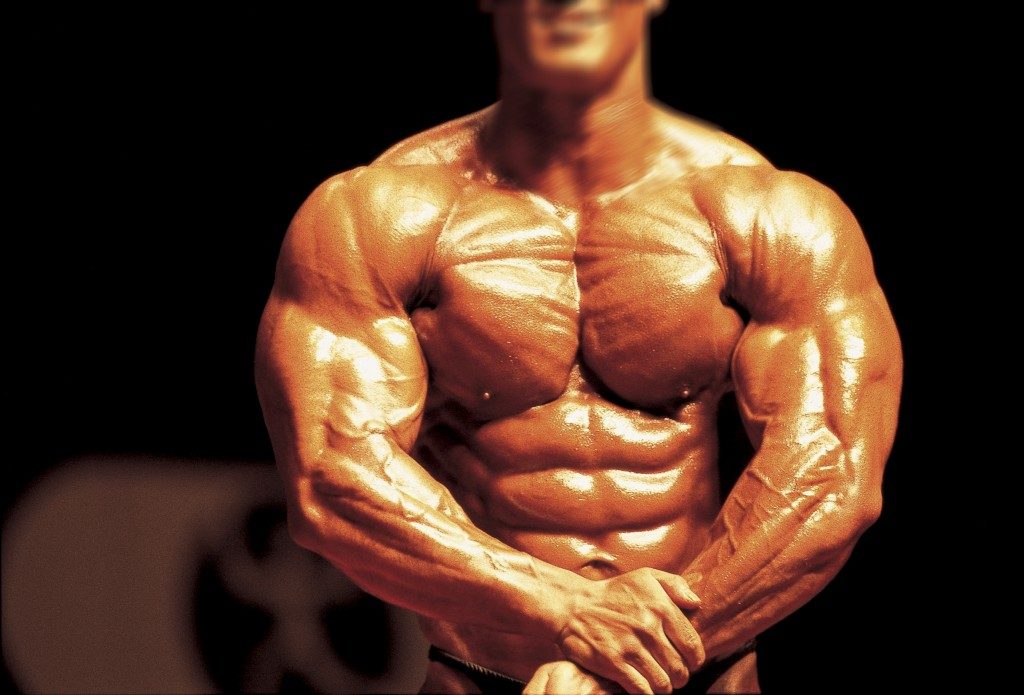

This is all par for the course. Every art has its great masters—painting its Da Vinci, film its Fellini. Every glitzy clique has its answer to the Oscars. What matters most is not the trappings. It is the work. Were bodybuilding art, it would most closely resemble sculpture. Indeed, exercises which shape muscles are even referred to as “sculpting.”

However, there is one important difference between sculpture and bodybuilding. It is the same reason why one does not call a live sporting event a documentary. Bodybuilding is presentative. It is what it is. Sculpture is representative. It shows what might be. And while both can be admired for the dedication necessary on the worker’s behalf, art always exists in the realm of possibility. Bodybuilding is as concrete as it gets. It only symbolizes its own accomplishment.

Some might interpret that as vanity, but vanity comes only from undeserved adulation. In the bodybuilder’s case, every fiber of muscle is earned through sweat. That is why strength exists not as art, but as the subject of art—it exists to inspire others towards their own accomplishments. Like Alexis Carrell said, “Man cannot remake himself without suffering, for he is both the marble and the sculptor.”