Why do we acknowledge First Nations lands and is it helping in the reconciliation efforts?

By Craig Allan, Contributor

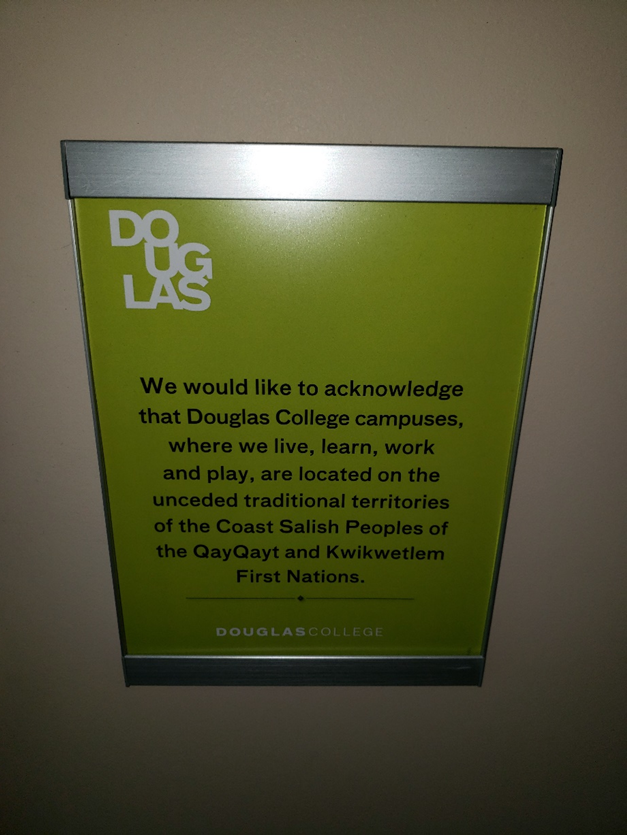

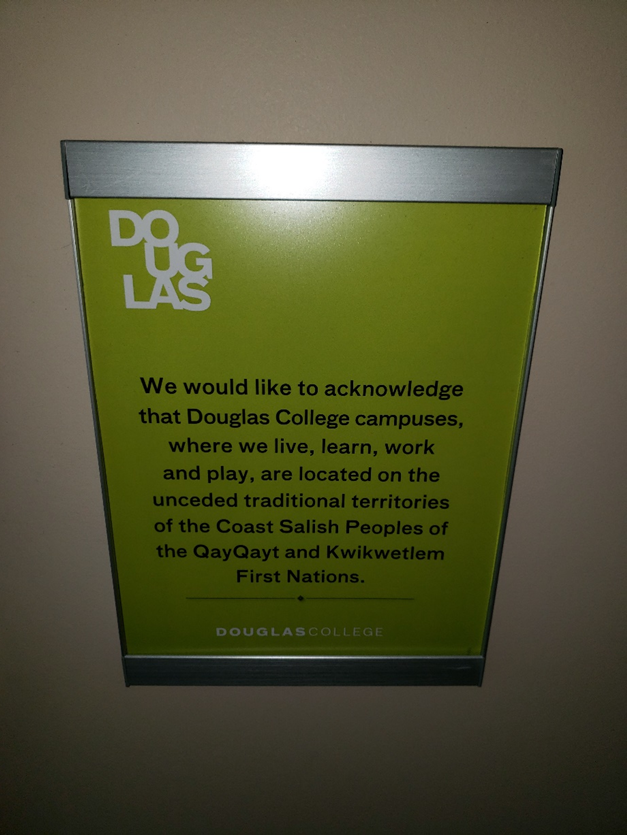

When walking out of a Douglas College classroom, you see many plaques and signs—maps showing emergency exits, signs that say no food or drinks are allowed in the classroom that mostly go ignored. However, there is another sign that has recently been added in the last few years that catches the eye: One that reads “We would like to acknowledge that Douglas College campuses, where we live, learn, work and play, are located on the unceded traditional territories of the Coast Salish Peoples of the QayQayt and Kwikwetlem First Nations.” This is just one of a wave of cultural and educational, and governmental, institutions that have made the acknowledgment of First Nations lands a staple.

With the recognition of First Nations lands becoming a standard practice in Canadian society, one wonders where the acknowledgment came from, why it is included, and if it has a positive effect on the reconciliation efforts in Canada.

Douglas College Aboriginal Coordinator Dave Seaweed said in an email interview with the Other Press that the acknowledgment “has moved to the forefront in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation report and the 94 calls to action.” Seaweed stated that from his own personal perspective, he feels excited when he hears the acknowledgment and proud of whoever has organized the event because it shows that the territory of First Nations people is being respected.

Douglas Student Union Indigenous Students Representative Caitlin Spreeuw voiced a similar sentiment in an email to the Other Press but also said that while the acknowledgment is “definitely a first step toward reconciliation […] there is still a lot more that can, and should, be done in order for true reconciliation to occur.

It’s worth noting that this official recognition is not as simple of a process as it may seem. For example, take the Acknowledgment of Territory document given to School District 40 by the Aboriginal Educational Advisory Committee. The document, which represents the QayQayt people who lived in the New Westminster area around Front Street, states that non-Indigenous people can acknowledge that the land they are standing on is First Nations land, but they cannot welcome people to the land. That duty can only be performed by a member of the First Nations group, or their descendants.

Ever since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report came out, Canadians have become more aware of First Nations people and their role in the shaping of the land. Canadians know more about the pre-colonial inhabitants of this country than they ever have before. The acknowledgments are proving themselves to be a valuable resource in connecting and transmitting knowledge because while older generations may have grown up with little information about the lands they occupy, the next generations will grow up with a better understanding of the people who lived on these lands first. It may seem like just words, but they are words that breed knowledge, understanding, and respect.