Sadly, the Pickton case revealed that missing women from the Downtown Eastside were not considered of high importance to police and society. The women had experienced hardship and struggled with substance abuse while working in the sex trade—not by choice but by circumstance.

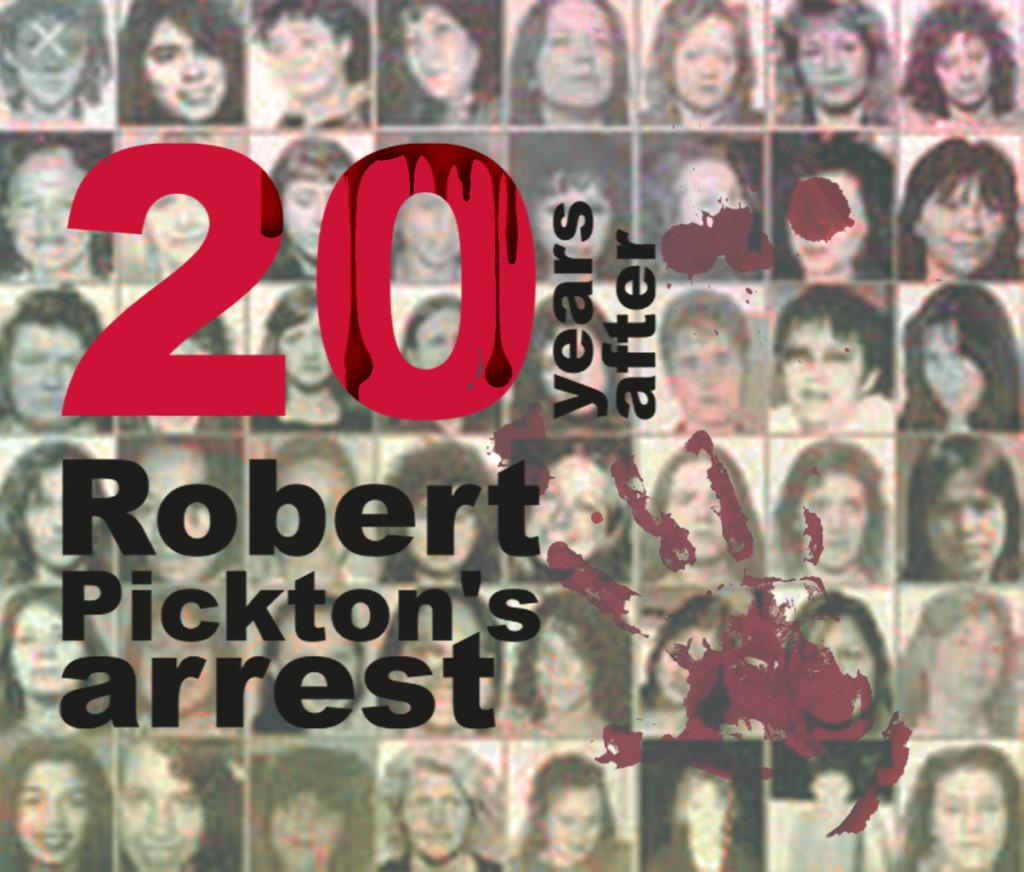

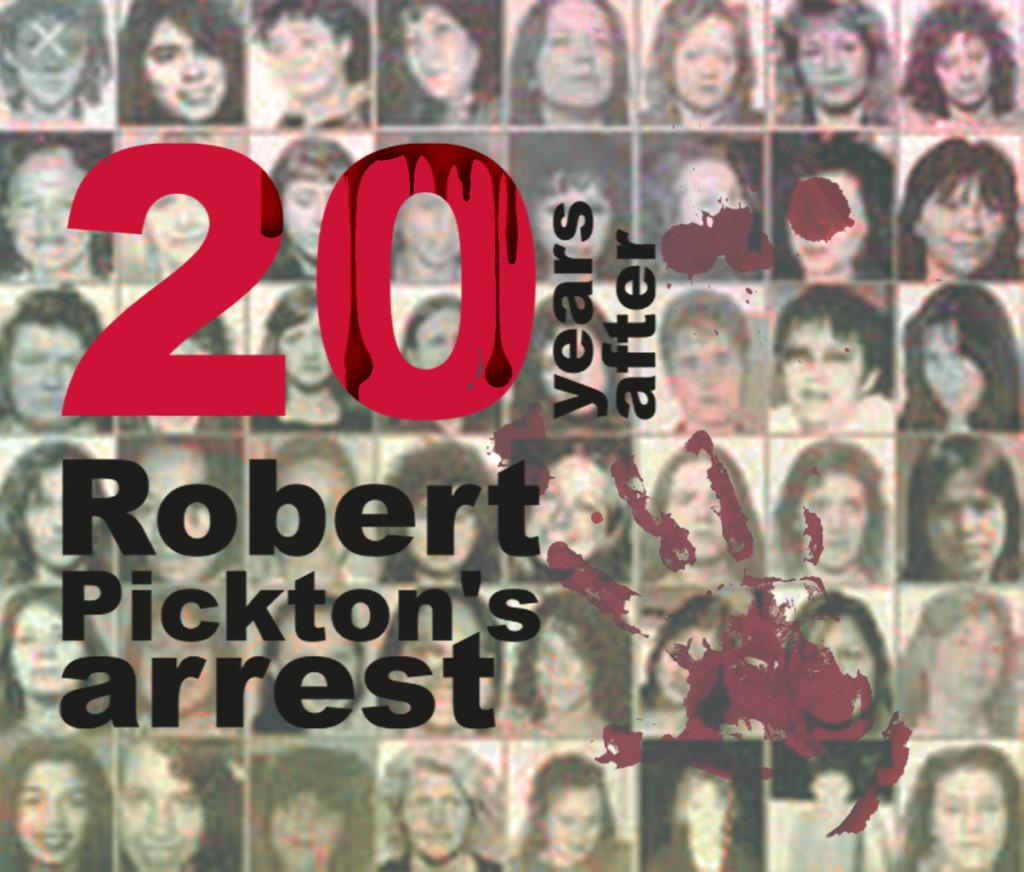

This year marks 20 years since Robert Pickton’s pig farm was seized by police

By Brandon Yip, Senior Columnist

When tragedy strikes, the turbulence, aftermath and damage often take time to surface. And that is what eventually occurred at a pig farm at 953 Dominion Avenue in Port Coquitlam. It was owned by Robert Pickton, one of Canada’s worst serial killers. His pig farm would mask a “house of horrors” and what transpired there would horrify the community. The farm would be the centre of one of the largest serial killer investigations in Canadian history.

February 2022 marks 20 years since Pickton’s pig farm was seized by the RCMP, working together with the Vancouver Police Department. They executed a search warrant on the property related to the use of illegal firearms as reported by Global News. Robert Pickton and his brother, David, were arrested and police obtained another warrant after what had been observed on the property. Police and forensic investigators would later discover human remains and DNA related to dozens of missing women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside—many of whom were Indigenous.

The Robert Pickton case generated headlines around the world. Media outlets worldwide arrived at the Pickton property to cover the story—as a plethora of news media vans congregated outside the property at the north end. The extensive investigation into the Pickton pig farm and subsequent gruesome discoveries on the property brought unwanted negative attention and publicity to the City of Port Coquitlam. Port Coquitlam is known as a quiet suburban city and a safe place to raise a family. Notably, the city is also the hometown of Canadian hero and cancer advocate, Terry Fox.

Unfortunately, Port Coquitlam now had a darker and more sinister reputation due to the Pickton investigation. There was an ominous tone in the community. Sadly, what the Robert Pickton case also revealed was how missing person cases were not a high priority with police. It appears this apathy and lack of initiative to follow up with women reported missing in the Downtown Eastside helped a predator like Robert Pickton roam freely and prey on women working in the sex trade with anonymity. Sandra Gagnon, whose sister, Janet Henry, was one of Pickton’s victims—told Global News in February 2022, she recalled the disrespect she received from an investigator from the Missing Women’s Task Force regarding her missing sister. “He said, ‘The woman [could not] get dates anyway.’ How dare he talk that way about our missing loved ones?”

Former Global News reporter, John Daly, was at the Pickton property when police announced his arrest. “We were called to the pig farm in [Port] Coquitlam, late one night,” he said to Global News in February 2022. “They had a massive news conference under a tent. They said they had arrested somebody who hadn’t been charged with any murders at that time.” Daly also recalled the frustrations from the families of the missing women. “It was a horror story and the families were right, they were ignored,” he said. “There were families who went to [the Vancouver Police Department] to report sisters and relatives missing and were told basically buzz off. They were on some kind of prostitution track and they were getting ignored.”

Robert Pickton was born on October 24, 1949. He was raised on a farm owned by his parents, Leonard and Louise. Along with brother David, he also had a sister named Linda. According to a Canadian Encyclopedia biography on Pickton, he and his siblings reduced the farm size to 6.5 hectares when they sold the majority of it for urban development. Pickton kept a small-scale livestock operation at the farm. In addition, he received a share of money made from real estate transactions. Pickton was known to be anti-social and oftentimes exhibited odd behaviour. He lived in a trailer home by himself on the farm. Additionally, in the late 1990s, Pickton held large parties on his property—known as Piggy’s Palace. It entailed live music and dancing. The gatherings were attended by approximately 1,700 people, including bikers and sex trade workers from the Downtown Eastside. In 2000, the City of Port Coquitlam shut down Piggy’s Palace.

Pickton also kept a tape-recorded journal, excerpts of which were played in the 2011 CTV documentary, The Pig Farm. He discussed what life was like growing up on his family’s farm. “We bought this here farm where we’re on here right now,” he said. “[It is] a 40-acre farm. We bought it back in about 1963 and-a-half. I had my experiences here. I got thrown [off] horses, I got tossed upside down. I got mauled by bulls. I got [torn] apart by wild boars. I’m telling you; I had my mishaps.”

As police continued searching Pickton’s farm, they eventually discovered pieces of women’s clothing, shoes, jewelry and an asthma inhaler prescribed to Sereena Abotsway—one of the missing women. DNA testing of blood found in Pickton’s trailer was from Mona Wilson. Pickton would be charged with two counts of murder (a total of 26 murder charges eventually laid against him). CBC News reported in a February 2018 article that the remains or DNA of 33 women were found on his pig farm. But the number of women Pickton allegedly murdered may be higher as evidenced in a prison surveillance video recorded in February 2002, with Pickton in custody—as reported by the Toronto Star in January 2012. He confessed to an undercover police officer (posing as his cellmate) that he killed 49 women. He had wanted to kill another woman to make it 50, but he said he got “sloppy.” Remarkably, the Canadian Encyclopedia stated investigators obtained 200,000 DNA samples and seized 600,000 exhibits. Forensic experts and archaeologists required heavy equipment to inspect 383,000 cubic yards of soil, searching for human remains. The total cost of the investigation was approximately $70 million.

CBC News reported in August 2010 that Pickton was well known to police in the 1990s. In March 1997, Pickton picked up a sex trade worker in the Downtown Eastside. The woman alleged that Pickton drove her to his property in Port Coquitlam; while at Pickton’s place, she claimed Pickton tried to handcuff her. She panicked and grabbed a butcher knife and stabbed Pickton—fighting for her life. He, in turn, stabbed her repeatedly. The unidentified woman ran away from the property and flagged down a passing car. She later recovered in hospital (Pickton also required hospital treatment). CBC News stated that Pickton was “…charged with attempted murder and forcible confinement in that case, but the Crown later stayed the charges, saying the woman was not a sufficiently credible witness.”

In December 2007, Global News reported Robert Pickton was convicted on six counts of second-degree murder in the deaths of Marnie Frey, Mona Wilson, Angela Joesbury, Sereena Abotsway, Brenda Wolfe and Georgina Papin. He was sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for 25 years. The additional 20 murder charges laid against Pickton would be stayed. Justice James Williams upon sentencing Pickton addressed the court as reported by CBC News. “Mr. Pickton’s conduct was murderous and repeatedly so. I cannot know the details but I know this: what happened to them was senseless and despicable,” he said as he read out the names of the six victims. “Mr. Pickton, there is really nothing I can say to express the revulsion the community feels about these killings.”

Williams then spoke about the six victims, stating they were women and human beings who were not given any dignity and respect: “The women who were murdered, each of them, were members of our community. They were women who had troubled lives. Each of them found themselves in positions of extreme vulnerability. They were persons who were in the ugly grasp of substance abuse and addictions, persons who were selling their bodies to strangers in order to survive.”

In December 2012, an inquiry into the handling of the missing women’s case was released to the public. The report was called the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry (MWCI) and was conducted by inquiry commissioner and former attorney general of BC, Wally Oppal. The report was critical of the RCMP and Vancouver police, stating they both failed to thoroughly investigate women who had gone missing from the Downtown Eastside. “The police investigations into the missing and murdered women were blatant failures,” Oppal said. “The critical police failings were manifest in recurring patterns of error that went unchecked and uncorrected over several years. The underlying causes of these failures…were themselves complex and multi-faceted.”

Oppal not only condemned the actions of police, but he also believed society as well should bear some responsibility for the women’s troubled lives. “I have found that the missing and murdered women were forsaken twice: once by society at large and again by the police,” Oppal wrote. “What we’re here to discuss is a tragedy of epic proportions. The women didn’t go missing. They aren’t just absent, they didn’t just go away. They were taken, taken from their families, taken from their friends, taken from their communities.… We know they were murdered.”

Sadly, the Robert Pickton case revealed that missing women from the Downtown Eastside were not considered of high importance to police and society. The women had experienced hardship and struggled with substance abuse while working in the sex trade—not by choice but by circumstance. The women were not respected and instead were being judged by what they did to survive. But the police and society also overlooked another important aspect about the missing women: that they were human beings. These women were someone’s mother, daughter, sister, aunt, cousin and friend.

Wally Oppal believes that more needs to be done to rid the stigma towards marginalized groups in our society. “Even though Pickton is in jail, the violence against women in the Downtown Eastside and other areas of this province continues. It’s time to end this violence,” he stated in the MWCI report. “It’s the inequality and the poverty that breeds the type of violence we’re talking about here. We need to treat those women as equals. That’s part of our duty as civilized people in a social democracy to ensure they’re accorded the same rights as everybody else.”

Global News reported that Robert Pickton will be eligible for parole in February 2024. Sandra Gagnon is outraged that Pickton is allowed to seek parole after the crimes he committed. “We have a rotten system,” she said to Global News. “[The] court system makes me sick.” In the meantime, Gagnon plans to fight any application for parole by Pickton. She is also authoring a book about her beloved sister and the other women who never came home: “I [do not] forget about our women because they were human beings. They were loving [and caring people]. Janet had a heart of gold.”

Remembering the suspected victims of Robert Pickton

Suspected victims of Pickton: Janet Henry, Mary Ann Clark, Diana Melnick, Cara Louise Ellis, Tanya Holyk, Andrea Borhaven, Sherry Irving, Helen Hallmark, Cynthia Feliks, Kerry Koski, Inga Hall, Sarah Jean de Vries, Angela Jardine, Jacqueline (Jackie) McDonell, Wendy Crawford, Jennifer Furminger, Tiffany Drew, Dawn Crey, Debra Jones, Patricia Johnson, Yvonne Boen, Heather Chinnock, Heather Bottomley and Diane Rock.

(Source: Global News)