Film review of VLAFF’s ‘Nothing More’

By Danielle Harvey, Contributor

From August 30 to September 8, the Vancouver Latin American Film Festival returned for its 11th year. As always, Douglas College’s New West campus was host to a special screening during the festival’s run, this year showing the 2001 film Nada, referred to as Nothing More in English. Students in Basic Spanish courses were asked to analyze the film, and selected below is Danielle Harvey’s topnotch review of Nothing More.

Cuban director Juan Carlos Cremata Malberti managed to captivate the audience at Douglas College with the September 4 screening of his 2001 film, Nothing More as part of the annual Vancouver Latin American Film Festival. A film filled with love, heartbreak, humour, and loneliness, Nothing More allows audience members the chance to relate to some aspect of the story, whilst providing an excellent example of how someone struggling with cultural and political traditions might manage to seek refuge from life’s difficulties and find happiness.

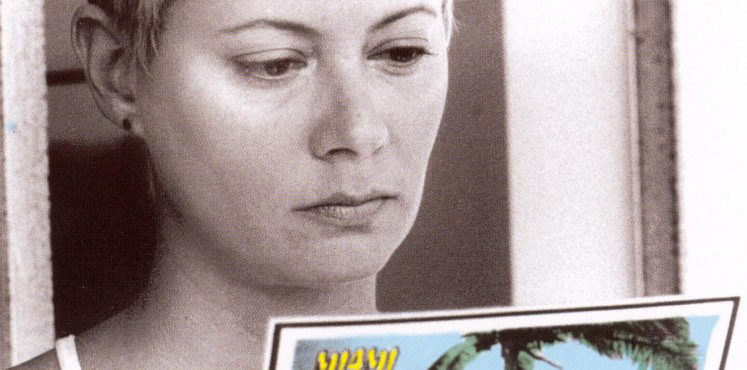

Carla Pérez (Thais Valdés) is a young Cuban postal worker who hopes of one day receiving the opportunity to finally reunite with her parents in Miami. Through her thoughts and actions, we witness the loneliness that has become a part of her life, along with the daily struggles of basic survival. At the beginning of this film, Carla represents a majority of the Cuban population: hardworking people with little to show for their efforts.

Another character of importance to this story is Cunda (Daisy Granados), the authority figure at the post office. Cunda has the power to create and enforce the rules at the post office; Malberti has chosen to use humour as a means of establishing this level of authority by creating pointless and absurd rules that the staff must abide by. In relation to Carla, Cunda represents something much more than just the working Cuban population. She represents the power within Cuba itself. She represents the Government, as the rules represent Cuban law, and the post office represents the country. With these two characters side by side in the film, we can begin to understand the impact and the struggles of this relationship in Carla’s daily life.

As we move towards the heart of the film, we witness Carla’s transformation of self through her actions. Carla begins to illegally intercept mail at the post office and rewrites thoughtful messages with the intention of being an anonymous source of happiness for people across Cuba; with time, Carla eventually sees the joyous impact she has had on the citizens of Cuba and is able to find happiness for herself. This is an excellent example of both human strength and human compassion: to find the strength to work and live through personal hardships can be a challenge on its own, but to go out of one’s way to be compassionate for others through these hardships takes much more. This implies that happiness is not something that we are born with; it is something that must be created and shared, whether it be through films, music, architecture, personal interactions, or in Carla’s case, words. Sometimes it is the simple things in life that make life worth living.

Throughout the movie, Carla’s happiness becomes more prominent as she begins to slowly change the world around her. As her happiness grows, music and dancing become a larger part of her daily life, writing becomes more frequent, close personal relationships are established, and, of course, there’s the visible physical transformation in her body language. Although these symbols of happiness are much more prominent, it’s the ingenious use of metaphor through colour that is impressive. The film is made in black and white, symbolizing the stagnant, uneventful, almost depressing life of Carla. As Carla begins to find happiness, colour begins to appear in certain frames throughout the film, mainly the colour yellow. The first place in the film where we see colour appears on the flower that sits on Carla’s desk at the post office, the place where she was able to harvest the notion of changing the world. After Carla receives the letter of Visa acceptance into the United States, the taxi that picks her up from her apartment is yellow, the start of her new life; different from the “new life” she has already created for herself.

Nothing More was a simple, yet informative reflection of Malberti and the life that so many people live, in Cuba and across the world. The storyline in this film is coherent and clear, aided by the brilliant use of colour, symbolism, and metaphors, but requires one to go beyond the literal narrative to really understand and benefit from the overall message. Malberti managed to communicate. One can only imagine that is what all artists aim to do: offer people the tools to think in other ways and evaluate one’s own life and experiences; Malberti succeeded. Happiness can change the world.