How I learned to stop worrying and love debt, parents, and unemployment

By Elliot Chan, Opinions Editor

It’s a cornerstone of North American culture to cherish independence; but how can parents really know when it’s the right time to strip off the training wheels and allow their children to go careering into traffic? How are the young adults going to balance work, school, and a social life while managing a household, or even just a small one-bedroom apartment? In this society, the ultimate proof of maturity isn’t a beard, a full-time job, or a college degree—it’s irreversible debt.

If you’re between the ages of 20-29 and you’re still living with your parents, relax—you’re in healthy company. The 2011 Census of Population by Statistics Canada reports that approximately 42.3 per cent of young adults in that age range are still living at home. This figure is much higher than it was in the past few decades, though: in 1991, the figure was 32.1 per cent, and in 1981 it was 26.9 per cent.

“Thirty is the new 20,” I remember some people saying when I reached the double-decade mark in my life. I wasn’t sure what that phrase meant then, but now I do. What they meant to say was that we now have until our 30s to get our shit together and build a life of our own. I must have wiped a bead of sweat off my forehead upon hearing that, feeling a bit relieved by the extra running room; but as it stands, with so many financial obstacles on the horizon, the dirty 30s may lead to more shameful realizations.

The quarter-life crisis

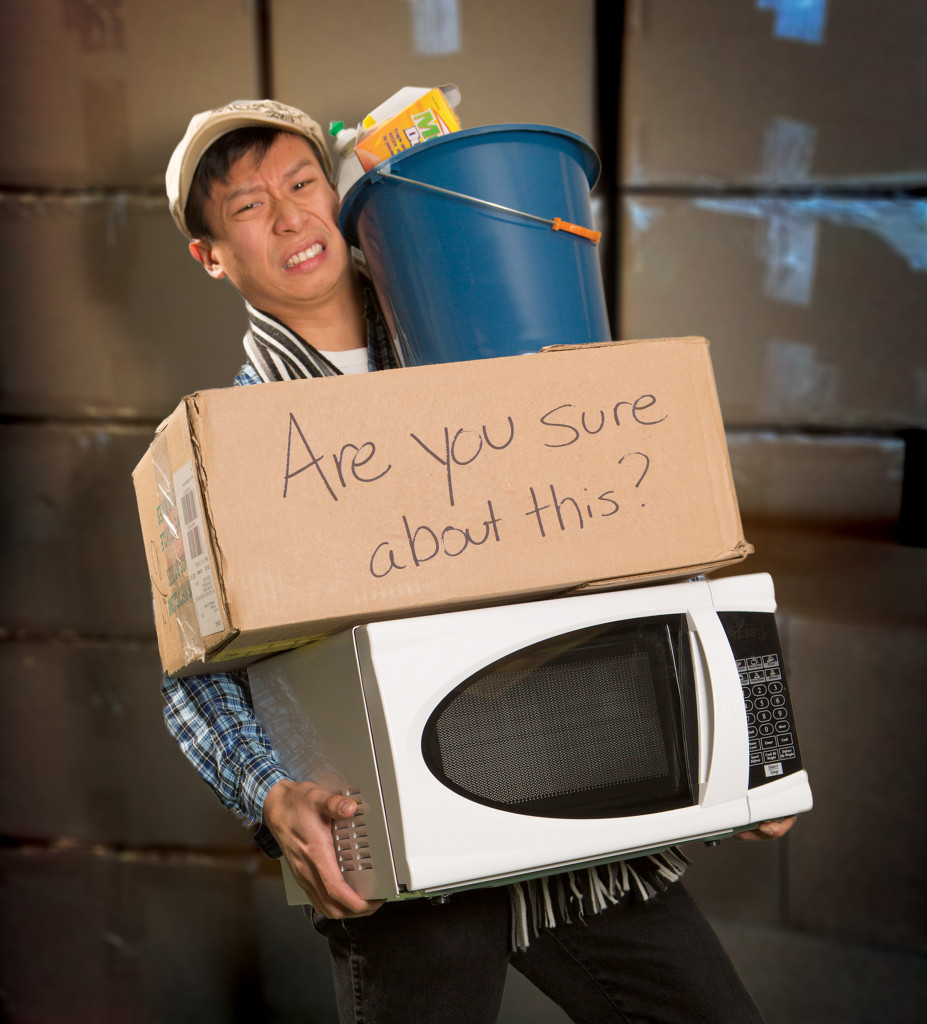

You did this to yourself—or maybe your parents and friends nudged you a little bit. Either way, you’re on your own now. No longer will your life magically clean itself when you’re off to school or work. Independence is an admirable trait, and most will respect you for it, but is paying your way through the hardest part of your life worth it? Taking a step forward is great, but you would hate to take two steps back.

Failure to launch is one thing; exploding in mid-flight due to a lack of preparation is a disaster all on its own. Or, at least, some will see it that way.

Progress is important. It’s what life’s all about, but there are no bad experiences as long as you learn something. Moving back home happens, and there’s nothing wrong with it. But how does one recover after such a defeat?

Whether you lost your job or got evicted, moving back home is an embarrassing endeavour. As disgraceful as it is, it still happens. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center showed that approximately 36 per cent of American millennials are living with their parents, thus labelling them the “boomerang generation.”

If or when you do return home and see the room you grew up in, nostalgia hitting you as fast as your mother’s nagging, remember that this is your chance to display some redeeming qualities. Don’t—I repeat—don’t fall back to old high school habits.

First off, you’re no longer allowed to whine about your parents. Consider another safety net: who else would catch you when you fall? There aren’t many choices.

That being said, you’re now entitled to have a lock on your door, if you didn’t have one before. You’ve created your own independence, and it’s important that you continue to keep your space separate from that of your parents’. Let them know that your room is sacred and should be respected, and vice versa.

Pay rent. Your parents will understand that you’re financially unstable—duh, you’re back home—but do chip in to show your appreciation. They may love you unconditionally, but they still deserve a retirement. Paying a bit of rent will mitigate the guilt.

Get out of the house as frequently as you can. Don’t loaf around waiting for an opportunity to knock on daddy’s door. Here is where you bounce back with grace. Seek work tenaciously, volunteer, intern, take a course, do anything to show your family that you’re not going to boomerang again—you’re going to slingshot.

The follow-your-passion generation

The social stigma of living at home with your mom and dad needs to stop. Parents need to understand the struggles that their children are facing. Since the recession in 2008, the unemployment rate for young adults has remained relatively unchanging—at about 14 per cent, says Statistics Canada. That might not seem high, but one in four working millennials with a college degree has a full-time job that doesn’t require it. Moreover, almost half of young people are in low-paying employment such as retail, food service, or low-level clerical work—none of which are enough to reverse student debt.

There are many names for our generation these days, but the one I prefer is the “follow-your-passion generation.” Some may see it as indolence or underachievement, but I don’t. It’s easy to settle and fall into a repetitive job and become a lifer, going from paycheque to paycheque, frugally supporting yourself and a family. Although student debt, the bank, and the Hotel of Mom and Dad may seem like a millstone with higher interest rates than expected, we must remember the ultimate goal: it might all be a ticket to a better life.

It’s not easy pursuing a passion. Even though you want to be the ultimate success story, the model of independence, and a perfect example of a self-made person, the fact is “self-made” anything is a complete fiction. Alter your values a bit: don’t just aim to be successful, be gracious as well. Accept help when it’s offered, and return it. After all, the hand that feeds you needs you.

The perfect storm for us millennials is unfortunate, and braving it alone can be daunting. Moral, emotional, and financial support can do more for young adults than a dingy $600 per month basement suite. Avoiding the risk of fostering entitlement and sloth, parents willing to accommodate their children until they have a firm footing must understand the difference between independence and interdependence. Parents must humble their children without discouraging, and support them without smothering.

Kids, don’t view your parents’ home like a probation office, because it isn’t. It’s your home, too. You’ve been living there for 20-something years. You might have had some chores now and then, but your mom and dad never counted on you to do any heavy lifting before. By contributing now to the mundane housekeeping, you’ll prep yourself for the inevitable. Just like the boomerangers, show your family progress. Regardless of the length of your stay, take them out to dinner and tell them about school, work, or anything else. Believe it or not, your parents really do want you to be happy—so quit complaining about how unfair life is.

Remember, as long as you’re contributing, you’re not mooching.

The third culture kids

The “third culture kids” phenomenon is becoming more prevalent today due to the high immigration rate throughout the past several decades. The best way to describe a “third culture kid” is with colour—bear with me: if parents from a blue country move to a yellow country and have a child, that child will grow up in a green world, thus trapped between cultures. I am a third culture kid, and I am currently facing the decision; should I abide by the customs of my ancestors, or of my home?

Occasionally, my parents will remind me of all their successes when they were young. After all, at the ripe age of 24, they were married, starting their own business, and had a mortgage and a child (me). I have none of that, but I do offer expertise that my parents don’t have. Whether or not they think of me as an investment is besides the point. The point is, I am their only child and sooner or later, due to Chinese customs, the responsibility will fall on me to take care of them; not some pension plan or retirement home—me.

That is the prevalent tradition in many countries, including Italy, India, and South Korea. In Anglo cultures, multi-generational households seems to be a burden, but it’s in fact highly beneficial. These households create their own little community, where each member plays a certain role to minimize the stress and responsibility. To move out before marriage would be abandonment, and to families that practice this custom, they see shame in the defiance of responsibility—not in a lack of independence.

So here I am, in my mid-20s, dreaming the Canadian dream, torn between what I want, what my family wants, and what society deems respectable. So the decision, like my bed, remains unmade: should I stay or should I go?