They’re brutal, bloody, and brilliantly entertaining

By Caroline Ho, Arts Editor

The subgenre of “grimdark” probably seems a bit self-explanatory based on the term itself. It’s a category of speculative fiction—usually fantasy—that’s unapologetically gritty, unromantic, and depraved in very human ways. What its novels lack in moral messages and optimism, they more than compensate for with cynicism and gratuitous violence. At first glance, grimdark and supernatural horror or dark fantasy might seem to have considerable overlap, but we can usually draw a few (nebulous) distinctions between them. Horror tends to aim at shocking and scaring the reader, and mostly deals with supernatural aspects that actively work against the protagonists. In grimdark on the other hand, the main forces acting against the characters are often their own tormented personalities.

I love epic fantasy, but anyone who’s familiar with the genre has to acknowledge that it’s full of tropes—orphaned, prophesied heroes, and wise, wizardly mentor characters pitted against the Bad Guy in a heroic light-vanquishes-dark quest. Instead, grimdark gives you bitter old veterans, self-satisfied cowards, unsympathetic bigots, sociopaths, and sadists. Stories are usually constructed to consciously subvert fantasy tropes. This isn’t to say that grimdark precludes fantastic elements, and in a lot of books and series, the setting, systems of magic, and scope of conflict are just as epic as your traditional fantasy. However, characters are often apathetic about the fate of the world, if not actively trying to dominate or destroy it.

One series often touted as a pioneer of grimdark and an inspiration for many later authors is Glen Cook’s Black Company, starting with the first novel of the same name published in 1984. The series features a band of mercenaries who fall into the employment of an ancient evil sorceress known as the Lady. The seemingly predominant theme of this series is one that the characters themselves grapple with repeatedly: the question of evil and relativity. The Company is tasked with combatting the Rebel, a resistance army fighting against the oppressive reign of the Lady; but it’s clear that the Rebel is no force of virtue either, and both Rebel and Lady are probably less manifestly terrible than the Lady’s long-dormant husband, the Dominator. Is there such a thing as fighting for a lesser evil, when everyone is irredeemably corrupt? The Black Company assaults the reader with an endless mix of merciless conflict and moral challenge.

Probably the most mainstream grimdark author currently is George R. R. Martin, if you consider A Song of Ice and Fire to be grimdark, as it’s often categorized. The series is definitely a stark enough divergence from the Tolkien or C. S. Lewis brand of fantasy, given the levels of violence, rape, and seemingly-excessive human cruelty.

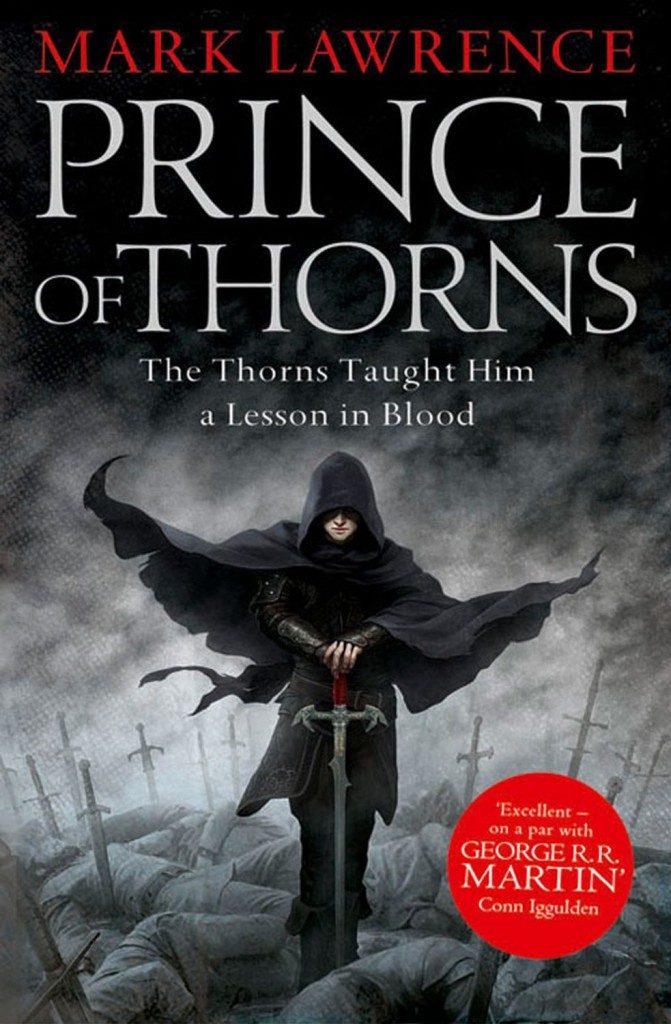

Other fantasy writers usually labelled as archetypal grimdark authors are Mark Lawrence and Joe Abercrombie. Lawrence’s Broken Empire trilogy follows one of the most unforgivingly brutal protagonists you could find, 13-year-old Jorg Ancrath, who leads a band of thugs and murderers and commands their respect by being the most thuggish and murderous of them all. Abercrombie’s First Law trilogy is probably the most brilliant example of a clever subversion of fantasy tropes—featuring wise old wizards, adventuring (anti)heroes, and plot twist after plot twist that leaves you repeatedly feeling like everything that you love about the fantasy genre is trite and meaningless.

A lot of the biggest fantasy series in recent years have been labelled as grimdark: R. Scott Bakker’s Prince of Nothing, Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen, Scott Lynch’s Gentlemen Bastards, and many more. The popularity no doubt stems from ASoIaF in part, and the trends of publishers to promote books with similar atmospheres in the hopes of similar success. And, of course, with every big artistic or literary trend, plenty of critics out there claim that grimdark is too much of a broadly-applied buzzword, that the genre’s oversaturated, or that all of this morbidity and moral degradation is probably corrupting our kids.

So why read grimdark, if it seems to be nothing but corrupted, self-loathing characters and nihilistic themes? Why read any piece of literature that challenges, provokes, and explores the most despicable traits of humanity? Maybe because there’s something morbidly fascinating and undeniably meritorious in entering the minds of the twisted and tormented, whatever the genre. To anyone who’s tired of hearing fantasy regarded as fluffy escapism, a retreat from “real” problems into a world where everything is rainbows and a bit of spellcasting solves any problem, grimdark is the answer.