British Columbians have until November 30 to cast their vote

By Katie Czenczek, News Editor

With voter packages being sent out starting last week, it is the perfect time to discuss the provincial referendum.

From now until November 30, British Columbians will have their say in how to elect candidates and parties. The referendum is designed to have two different questions that people will answer via a mail-in survey. Your voting package should turn up between October 22 and November 2. The first question that will be asked is if we should keep our current first-past-the-post (FPTP) system or move to a system of proportional representation in British Columbia. Whether or not you support FPTP, the second question will ask what your preference is between the three proposed proportional representative voting systems.

The three proposed voting systems are Dual Member Proportional (DMP), Mixed Member Proportional (MMP), and Rural-Urban Proportional. Of these three, MMP tends to be the system that people who want to keep FPTP lean towards if they have to switch. DMP is a new system designed specifically for British Columbia’s situation—one aspect that was kept in mind when making it is the province’s large geographic region.

Judy Darcy, the Minister of Health and Addictions and New Westminster’s Member of the Legislative Assembly, said in an interview with the Other Press that she feels switching to a proportional representation system will make it more worthwhile for people to vote in provincial elections.

“There’s a lot of cynicism about politics and about elections, especially amongst young people, and I can understand why,” she said. “You’re forced into this position of voting against something versus voting for something you believe in. Our present system forces you to do that.”

Darcy was referring to strategic voting—a voting strategy where a person votes to prevent a candidate they don’t support from being elected, rather than voting for the party or person that they prefer. In other words, it’s a preventative measure to attempt to keep a party they dislike out of office by voting for the party most likely to win against the disliked party.

FPTP is our current voting system that falls under the winner-take-all category. In BC, this has led to governments being elected as majorities with merely 40 percent of the vote. According to FairVote’s website, out of the 195 countries in the world, 89 of them use some form of proportional representation. Canada, the US, and the UK all use a “winner-take-all” system. Countries such as Norway, Sweden, Spain, Peru, and Angola all use some form of proportional representation. Although this BC referendum does not impact the federal vote, it still may change how the province elects its leaders.

Darcy also said that getting away from FPTP might enable politics to become more cooperative, since there are likely going to be fewer majority-run governments in the province.

“If you have a majority of seats, you can do one hundred percent of what you want to do,” she said. “You don’t have to consult with anybody, you don’t have to negotiate with anybody, you don’t have to compromise with anybody, you can have my way or the highway, and sadly, that’s what it has been in this province for 16 years.”

She also said that what she likes about proportional representation is that having to compromise makes for more voices being heard throughout the province.

“It forces you to negotiate, and I think that makes for healthier and better public policy in the end that is more reflective of the population as a whole.”

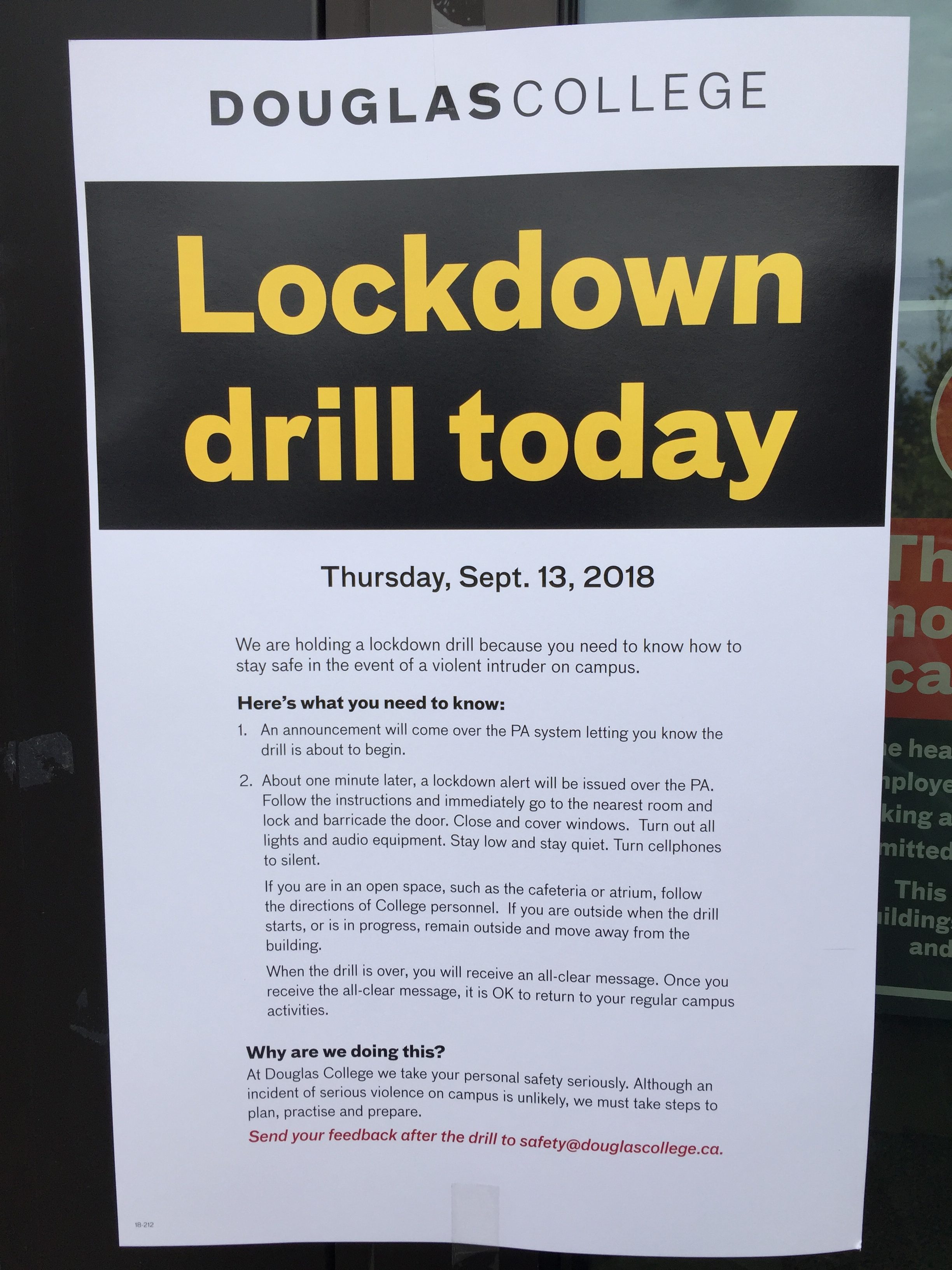

On October 23, Douglas College hosted an event in the Aboriginal Gathering Place at New West campus to break down the differences between proportional representation and FPTP. SFU professor Eline de Rooij was the guest speaker at the event. She explained the history of voting in BC and dispelled some of the myths surrounding the voting systems being called to question. On the following day, Douglas College also hosted a debate between supporters of proportional representation and FPTP.

De Rooij said during the talk that she doesn’t believe there is a perfect system out there that will make everyone happy.

“There is no best system,” she said. “There are systems that differ in what they’re good at. For all of you, it’s a matter of figuring out what you find most important and voting for a system that is best at what you find most important.”

She then broke down the differences between the three proposed voting systems in conjunction with FPTP. In addition, she stated why the referendum is important and the kinds of things that it will decide.

“It determines who gets to hold the power and who gets to be the opposition,” she said. “It’s related to stability of our governments, to decision-making powers our government has, to the clarity of responsibility—that we know whose fault it is if things go wrong, and as well as who is represented in government.”

De Rooij explained that there are pros and cons to each of the voting systems, and that there will likely be more parties represented in the legislative assembly. She also said that there is no guarantee that voter turnout, diversity in office, or cooperation will improve after the referendum. A drawback to proportional representation may be that governments might hold less accountability.

“The electoral system is not the cause all of these ills, nor does changing the electoral system solve these problems, she said. “We’re very likely going to get more parties into the assembly and more coalition governments. The downside of that is that there might be less responsibility-taking by governing parties.”

She also highlighted that policies might not be as quick to change, but that change might be more permanent than it is under FPTP.

“There might be a more deliberative and slower policy change, when compared to the policy lurches you see now between governments,” she said. “If parties have to work together, they can’t change policy as quickly. The positive side of that is that they can’t go back and forth over policy.”

De Rooij warned during her presentation to be wary of the myths put forward by those for and against proportional representation. As an example, she discussed the notion that FPTP is less likely to elect fringe and/or extremist parties.

Darcy also addressed this notion and said that people can use recent elections in Canada and the US to show that FPTP does not prevent fringe governments from being elected.

“The present first-past-the-post system elected Doug Ford in Ontario. End of story. First-past-the-post elected Donald Trump in the United States. My case rests,” Darcy said. “Under the legislation that has been passed [for proportional representation], a party would have to get five percent of the vote in order to have seats.”

One thing that both de Rooij and Minister Darcy both emphasized is that if people vote yes for proportional representation, in two terms’ time there would be another referendum that would allow British Columbians to go back to FPTP or keep the new system. For more information about the systems, visit elections.bc.ca to get non-partisan information about the proposed systems, or check out the information provided in the voter’s package.