A conversation about Día de Los Muertos

By CJ Sommerfeld, Staff Writer

“Celebrating Día de Los Muertos shapes the way you perceive death as only another step through existence and not as the end of it.”

The spookiest time of the year has just passed, and yet zombies, graves, and other deathly ideas still loom in the air. But have you ever thought that our gloomy association with death is simply a cultural construction? Some societies commemorate the loss of life, such as Mexico and their Día de Los Muertos.

To many, death connotes melancholic emotion. We frequently believe that when someone has physically left, it is unlikely that we will ever see them again. Día de Los Muertos—what many may know as the Day of the Dead—is an Aztec tradition that instead celebrates the time which individuals spent alive. This celebration is still practiced in Mexico to the present day. The Other Press spoke with Mexican-born Luis Fernando Santana Andrade on both this festive night, and the commemorative perspective in passing.

Día de Los Muertos occurs on November 2 each year, and although its date is close to Halloween’s and their themes appear similar—the two holidays contrast greatly. Santana Andrade notes that while Hallow’s Eve focuses on the frightening components of spirits and fictional characters such as Frankenstein, Día de Los Muertos instead honors and memorializes the spirits.

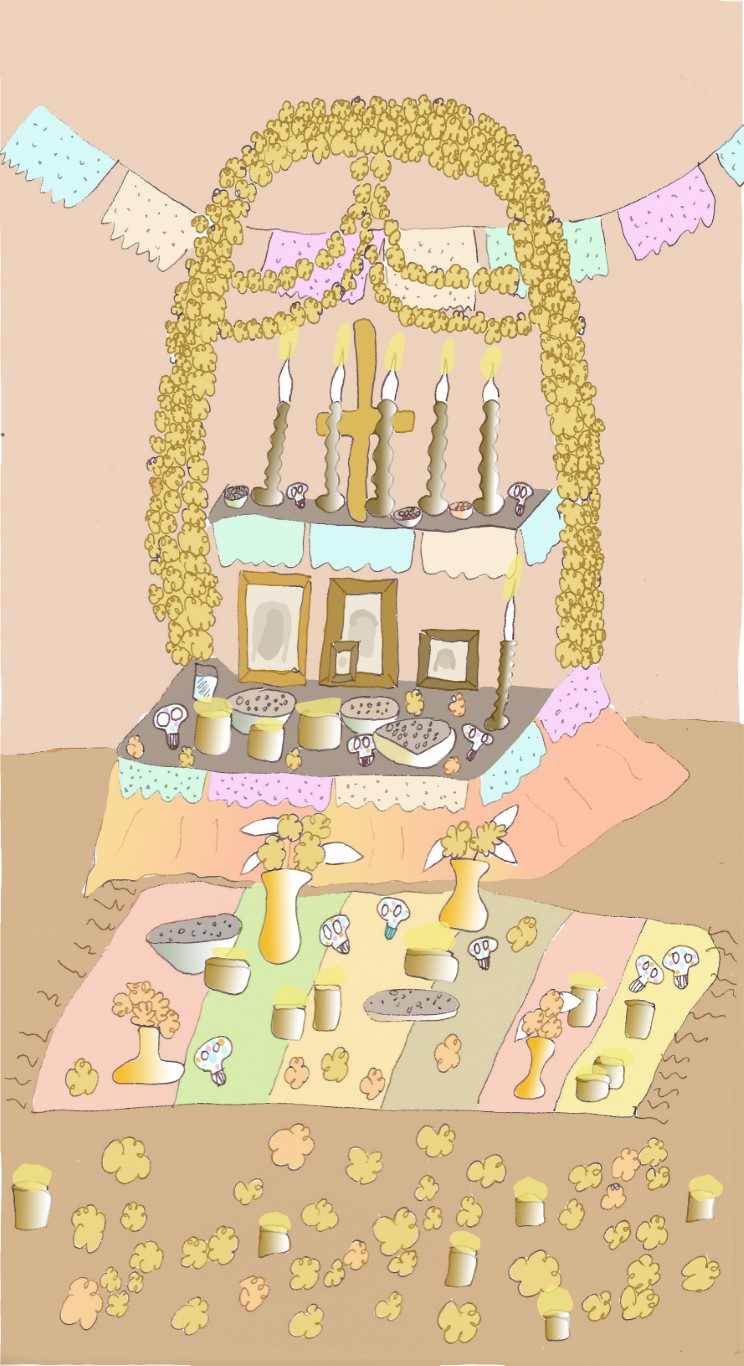

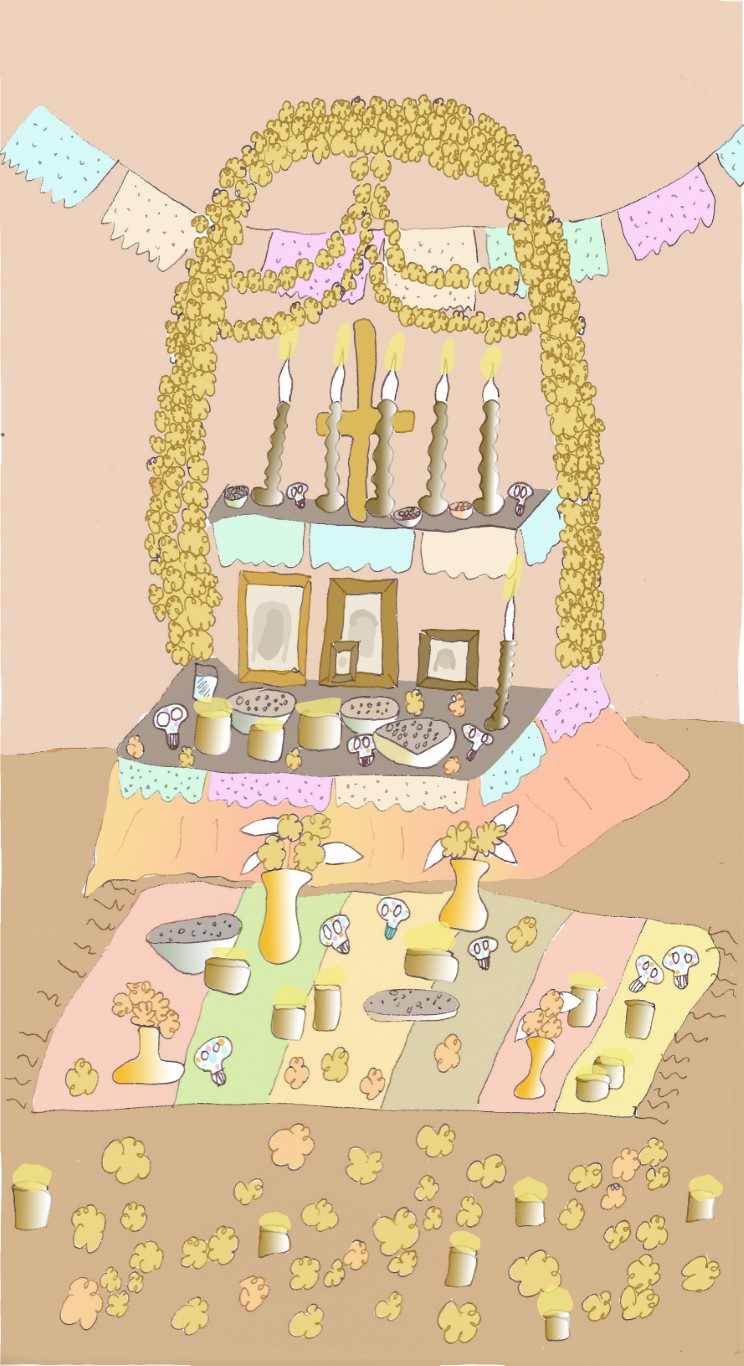

Families do this by embellishing ofrendas (alters) and graves with cempasuchíles (marigolds), dulces (candies), Calaveras (sugar skulls), tequila, pulque, and an assortment of their favorite foods from when they were earth-dwelling. The purpose of decorating the alters and graves this way is to entice the spirits to return to Earth during this evening. It is believed that the returning spirits do eat the food, although the food still physically remains. It is also said that no nutrients within these foods endure the night.

Photos of the deceased are placed atop the alters and graves; the paths are outlined by candles and more marigolds. All of this is done to aid in leading the spirit’s way after their long journey from the Aztec afterlife, Mictlán. It is known to be a long trip back to Earth and it is for this reason why sugar water and candies are left out for them to indulge in when they do arrive.

Mexico was being colonized by Spaniards by the 1600s, however, Día de Los Muertos is rooted in the country’s early Aztec roots. With the Spaniards being Christian—a religion whose views of the afterlife differ greatly from those of the Aztecs—components of such has washed over the indigenous celebration. It is this version—a hybrid of Christian and Aztec tradition that people celebrate present day. Fortunately, one thing that has been preserved is their enlightening view on death.

Santana Andrade notes that while crosses are used to embellish the alters and prayers are sung, the original essence of Día de Los Muertos remains. He reminds us that the church has not accepted a heaven that would allow spirits to return to the material world as they are thought to do on this night, demonstrating that the Aztec’s beliefs reign victorious.

Andrade explains the differences that he has noticed in the perception of death in those who celebrate Día de Los Muertos and those who do not. He notes that those who did not grow up in Mexico and have not experienced this tradition first-hand do not like to mention death—Western culture tends to exclusively experience torment and loss when dealing with the notion. He contrasts this view with those who practice Day of the Dead traditions: “Celebrating Día de Los Muertos shapes the way you perceive death as only another step through existence and not as the end of it.”

Halloween’s notions surrounding demise are often associated to fear. The tone of the holiday can easily initiate feelings of gloom, so why not adopt this tradition’s heartening view to veer from the murky emotions that result from the way many of us have been conditioned to perceive loss.