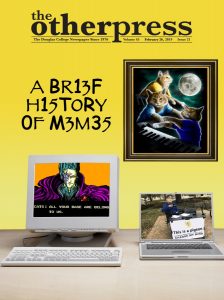

From dancing babies to whatever’s happening on TikTok right now

By Bex Peterson, Editor-in-Chief

Meme culture is so pervasive that I think people take its ubiquity for granted.

Nowadays, everyone is in on it. You’ve got “wine mom” memes, memes for nerds, marketing memes, memes for just about every profession out there—if you want to get really obscure, I’m part of a meme group on Facebook specifically geared towards music engravers. “Sibelius is an objectively good music composition and notation software,” amirite guys?

It wasn’t always like this. The rise in popularity of memes is, of course, concurrent with the rise of the internet as a minute-to-minute aspect of our daily lives. Smartphones allowed us to take the internet with us wherever we go. Again, it seems strange to marvel at a SkyTrain full of people checking Twitter and Facebook on their phones, but this simply wasn’t our reality even just 10 years ago.

I know this because I remember what meme culture was like in 2009. I was there, Gandalf. I was there for LOLCats, FAIL Blog, Rage Comics, and Philosoraptor. I remember when auto-tuning viral videos was the fresh new comedy offering on YouTube (in amazing, high-def 480p), and I could recite the entirety of the “Leeroy Jenkins” meme beginning to end. I was there before that too—on Newgrounds and other early video hosting sites for Badger Badger Badger (not to be confused for Honey Badger) and yes, unfortunately, Salad Fingers. Thanks for the nightmares, David Firth.

I remember there was also a time where people would get pretty uppity about conflating “viral videos” with “memes.” My previous paragraph would not have flown on the message boards of yore; there was a clear difference between “going viral” and “becoming a meme.” Nowadays, they seem to largely amount to the same thing. Viral properties tend to spawn memes, by the very nature of what memes are.

Which of course raises the question—what exactly are memes?

Richard Dawkins was the first to approach the subject of “memes” in social theory in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Dawkins’ “meme” was a broad term to explain the phenomenon of how “cultural information” spreads—often through the use of repeated symbols or mannerisms passed along as people interact with one another. It’s far more complicated than that, but you can see the roots of where the term was appropriated into its modern context. Mike Godwin (yes, of Godwin’s Law) was the one who took Dawkins’ term and applied it to internet culture in a 1994 issue of Wired magazine, as early memes started cropping up in email chains or on message boards.

The “Dancing Baby” meme is often credited as the very first viral video/meme; however, given how memes were spread at the time, it’s virtually impossible to pinpoint any viral sensation as being the “first.” The Dancing Baby—also known as “Baby Cha-Cha”—was a 1996 short video of a CGI baby dancing to “Hooked on a Feeling” by Blue Swede. The video was largely shared via email before, according to KnowYourMeme.com, it was compressed into a GIF file and sent out further into the reaches of the World Wide Web.

It would take many, many pages to do a thorough timeline of memes and viral web content, but I can do a quick overview and hit on some of the old favourites. If you remember “The Hampsterdance” from 2000—congratulations, you’re old now, but more excitingly you remember another prominent early internet meme! Even more excitingly, the meme was originally created by a Canadian: Deidre LaCarte of Nanaimo, British Columbia, who created the “Hampsterdance” in 1998 as part of a competition with her best friend and her sister to see who could attract the most internet traffic. The original web page was simple, just a line of gifs of spinning and dancing cartoon hamsters set to a 9-second, sped-up sample from the song “Whistle Stop” by Roger Miller (and yes, it’s the song that plays over the opening credits of Disney’s Robin Hood). The web page went viral in 1999 and attracted the attention of the Boomtang Boys, a Canadian band, who produced and released a full-length song based off the sample and the web page in 2000.

Video hosting sites such as Newgrounds helped provide a stable platform for viral videos such as the explosive “Numa dance” video in 2004. Meanwhile, official dark hellhole of the internet 4chan.org launched in 2003 and is said to be the originator of Rickrolling, LOLCats, “Chocolate Rain,” and more. The site has also acted as a breeding ground for some of the absolute worst the internet has to offer (much of the rise of the alt-right can be traced back to the anonymous nature of 4chan’s message board system, but that’s another article entirely).

Of course, the real Juggernaut of viral videos is the site, the myth, the legend: YouTube, the ultimate video hosting site. There’s not much to say here that isn’t already widely known, other than that it was founded in 2005 by PayPal employees Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim. Over 14 years it has transformed from a simple video hosting site to an enormous platform for content creators—who needs MTV when everyone’s uploading their music videos to YouTube these days?

Which brings us into the mid- to late ’00s, which is when I started getting into this whole “meme” thing. I think my experience is relevant as we circle back to the central question, “What are memes?”

I spent an entire summer as a 15-year-old starting every day by scrolling through a collection of blogsites, all under the Cheezburger Network—and yes, cringing at the name is an entirely natural response, as the joke was old even back then. The Cheezburger Network hosts approximately 50 sites today according to Wikipedia. Back in the day, the blogs were split into different types of popular meme categories: Demotivational Posters, FAIL Blog, Picture is Unrelated, Photobombs, Rage Comics, and many more. All of this is now stored under the Memebase site, which frankly looks as though it’s seen better days.

All these memes were recycled from chan boards, and the content wasn’t exactly fresh or innovative. However, memes and viral videos had this sense of being part of an insider culture; a meme would get recycled over and over again to a point of fascinating abstraction, where you’d get a bit of a zing to recognize the in-joke even after it had been reduced to its most basic form. The best example I can think of to showcase this phenomenon is this:

“I II II I_”

To some—I imagine most—readers, that progression of symbols will make absolutely no sense. But for some, I imagine you know exactly what I’m referring to: An infamously terrible four-panel update of the gamer webcomic Ctrl Alt Del, in which one of the main characters discovers his wife has suffered a miscarriage, pictured below:

The tonal dissonance of the serious subject matter combined with the overall art style and typically light tone of the comic made this four-panel sequence a target for mockery since its release in 2008. The comic has been parodied again and again to such an extent that if you’re an avid consumer of memes, the reference does not need to be any more oblique than a few “I”s in a row, followed by an underscore.

This is common in most meme circles. The music engraver meme I shared at the top of this article has devolved to a point where people will post objects with music notes plastered on them with the caption “______ is an objectively good-” and nothing else. We know what the poster is referencing, but Lord help anyone else diving into that space for the first time.

And I think, really, that’s what memes are: Shorthand. As Dawkins observed in his original conception, memes are meant to convey a large amount of cultural information in a small package. Memes give us an “inside joke” feeling—in the 2012 geek anthem “I’m the One That’s Cool,” Felicia Day proudly proclaims that she’s “Got my in-jokes you won’t get / like Honey Badger, Troll Face, and Nyan Cat” (a lyric that has aged about as well as those memes have). The incredibly short half-life on memes is part of the appeal; the moment the in-joke becomes too well-known, it loses that insider element. Memes tend to die the moment they’re referenced on talk shows and by anyone over the age of 25 (if I’m being generous). In the age of the internet during which we are constantly bombarded with information, the discovery, evolution, and degradation into obscurity of a meme is a lightning-fast process. Unless you’re constantly tuned in—which, in fairness, many of us are—there’s really no keeping up.

I’ve always found memes fascinating as a broader reflection of our socio-cultural experiences. We share these jokes into obscurity until all meaning completely disappears, or we abandon them. I think it says something really interesting about how we communicate with one another—not in a bad way at all, but rather as an indication of how we like to share with and understand each other.

But honestly, it’s probably not even that deep. Memes are fun. We, as a species, enjoy things that are fun. Maybe it doesn’t have to mean anything.

Which goes into another point I’d like to make about how millennial and Gen Z humour is a modern reflection of the mid-20th century Dadaist movement, but that’s a whole other topic altogether.