A personal essay on cultural identity

By Bex Peterson, Editor-in-Chief

In an area with a high immigrant population like the Lower Mainland, you get the question “Where are you from?” a lot as you’re growing up.

I come at this from a lens of whiteness that needs to be stated first and foremost before anything else. Coming from a family of white immigrants—especially white British and Irish immigrants—makes for a completely different experience than that of people of colour. One of my friends has Japanese ancestry and has been asked every painful and wrongheaded question about it you can imagine; she is not assumed to be Canadian the way my identity is largely assumed to be Canadian, despite the fact that her family arrived in British Columbia almost a full century before mine did.

But yes, I have been asked where I’m from many times. My looks would be classified as “Black Irish”—a fraught term, given that Black African-descended Irish people certainly exist, as well as the Afro-Caribbean community descended from Irish settlers who are also referred to as “Black Irish.” Black Irish was a term I was raised with, described to me as referring to Irish people with black hair and pale skin, such as myself. It’s one of many things I’m reflecting on as I grow older. Some identity terminology can harm and erase, and only serve to muddy the waters. Is this one of them?

The Irish Catholic identity matters to me because of the ways it’s affected my family. Those stories aren’t mine to tell but suffice to say the Troubles had a direct impact, the sort of impact that results in ripples down the family line. Identity grants context for a broader story that you, as an individual, only make up a few pages of. You are a product of a larger narrative, whether you wish to be or not.

If I ever visit Ireland, however, and someone were to ask me where I was from, I wouldn’t say I’m Irish. I would say I’m Canadian (a term that, given the ongoing effects of imperialism and colonialism, is also incredibly fraught). Again, so much of identity is largely about context.

So, what is the context of having Irish ancestry, especially in North America?

Some context

I mentioned the Troubles earlier, and I’m acutely aware that that part of history isn’t exactly universal knowledge in this part of the world. Allow me to provide a far too brief, far too simplistic overview.

First things first, some geography. Northern Ireland is a separate country from the Republic of Ireland—which is often referred to as simply “Ireland.” Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom; Ireland is not. The two countries share an island (also called Ireland, or Éire in the mother tongue) and a history of invasion and subjugation. Anti-Irish sentiments date back to 12th century and the Norman invasion of Ireland. In more modern iterations (19th and 20th centuries) the prejudice was largely rooted in anti-Catholicism and classism, as many Irish peoples experienced vast levels of poverty under British colonial rule. The stereotypes still exist today; the “drunken Irish” for one, which is certainly one way to depict the issue of generational trauma-driven alcoholism in the country; the “violent Irish” for another, seen in the names of popular cocktails such as the “Irish Car Bomb.” For a while, the “Irish terrorist” was a popular well to dip into for action movies, especially during the Troubles.

The Republic of Ireland gained independence from the British following a war fought between 1919 to 1921. This war was preceded by the 1916 Easter Rising of Irish republicans (not to be confused with the politics of modern-day American republicans—again, identity hinges on context, and the context here is quite different), which was quickly quashed by British forces. After independence was achieved, Ireland was split between the Catholic-dominated Republic of Ireland and the Protestant-dominated (and largely more in-line with British identity and values) Northern Ireland, which remained a part of the UK.

However, there were still plenty of Irish Catholics in Northern Ireland who resented the splitting of the country and wanted a united Ireland entirely free from British rule. Irish Catholics were largely persecuted in Northern Ireland, with the typical methods of systemic injustice including housing discrimination, job discrimination, and police brutality as a result of underrepresentation within the force. Civil rights movements in Northern Ireland in the ’60s alongside sympathetic marches and actions in the Republic of Ireland protested these injustices.

Fearing that the Irish Republican Army (who were major players in the Anglo-Irish war) might rise in Northern Ireland, several Protestant, British-loyalist/unionist paramilitary groups formed. Attacks on Irish Catholics by these groups—such as bombings and shootings—caused the civil rights movement to gain more traction; however, police action in response to attacks on Irish Catholics was slow to nonexistent. Unionist groups also planted bombs that they blamed on the then-dormant IRA to push the government to crack down on civil rights resistance.

After years of violence, riots, and protests, the Provisional IRA and Official IRA were formed in 1969 to combat violence from loyalist fringe groups and the government itself. The “Official” IRA believed that peace between Catholics and Protestants was necessary to achieve unification. The more violent “Provisional” IRA believed otherwise, to say the least.

What followed over the next few decades was the kind of horrific mess you can really only get from a civil war. Fighting between unionist and republican forces spilled over into the Republic of Ireland as well as the UK and even mainland Europe. Over 3,500 people were killed—mostly civilians. The war finally came to an uneasy “end” with the 1998 Good Friday agreement, although tensions still linger. This is why many Irish people are understandably wary of the potential consequences of the UK parting ways with the European Union. The Republic of Ireland is still part of the EU—if the UK pulls out, a hard border would have to be put in place between Ireland and Northern Ireland, which could result in fighting breaking out once more.

A North American context

According to the World Population Review, there are about 34.5 million Americans and 5 million Canadians with Irish ancestry. Compare this to the combined population of Ireland and Northern Ireland—just under 5 million, as of 2019 UN estimates.

Famine in the 1700s and 1800s (including the infamous Potato Famine) pushed mass migration from Ireland to the US, to Canada, and to England. Irish settlers in Australia included prisoners of war and criminals sent to the colony by the British. In the first push, Protestants made up most of the Irish settler population. Percentages of Irish Catholics and Protestants in North America would fluctuate over the centuries, and old grudges lingered—in Canada, sectarian violence broke out between the two factions in Toronto and New Brunswick in the mid-1800s.

Despite the decades—centuries in many cases—separating Canadians and Americans with Irish ancestry from the “homeland,” members of the diaspora tend to cling to the identity. If you ask them where their family is from, they will likely reply “Ireland,” even if this hasn’t been the case since the 1700s. It’s a common enough phenomenon that the Irish have a word for such people: “Plastic Paddy.”

As previously mentioned, the Irish have faced persecution and horrific injustices over the centuries. This applied to Irish migrants as well, especially in America, where Irish Catholics in the Midwest in particular faced systemic persecution. Unfortunately, many modern Irish Americans and Irish Canadians have taken this history and used it to provide themselves a context that absolves them of whiteness; “We faced subjugation too, and we have persevered” is often the narrative. It is not uncommon to see a North American with Irish ancestry lean in on issues such as cultural appropriation with statements such as, “Well, I don’t get upset about Saint Patrick’s Day and the Lucky Charms leprechaun, so why should Indigenous people be upset about racist caricatures as sports mascots?”

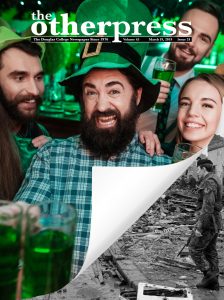

Many of these hot takes show up around Saint Patrick’s Day. I try to avoid the hashtag on Twitter when March 17 rolls around—there are plenty of Trump supporters there, waving Irish flags and drinking green beer and celebrating an identity with seemingly little understanding of the context.

And here is that context: Irish migrants have, since the 1800s, been assimilated into the construct of “whiteness.” We are white and we have white privilege. We are not, in North America, the downtrodden underclass fighting against a system that disadvantages us at every term. We are that system. But we seem to pretend, often, that we are not.

Michael Harriot, in an article for online magazine The Root, called out this narrative succinctly: “‘Whiteness’ isn’t real. Ultimately, race is a social construct, and ‘white’ is just some dumb shit that people made up a long time ago to build a fence around their idea of self-supremacy. The Irish didn’t suddenly calm down, put down the Guinness, put their noses to the grindstone and work their way into an exclusive club. […] Their melanin-less skin just afforded them an opportunity to blend in that [Black] people will never get.”

Irish identity is not an escape from being complicit—as a white person, as a settler on stolen territory. Experiencing historic subjugation due to cultural identity, due to religious identity, is not the same as experiencing ongoing systemic injustice due to skin colour. It is, as with most cases of identity, a matter of context.

My personal context

Why does my Irish ancestry matter to me?

There’s an argument to be made that it shouldn’t, as much as it does. My family is half English Catholic for one thing; for another, I was born in Canada. I have never set foot in Ireland. I only speak snatches of Irish Leinster—one of four dialects of a language that is considered by many to be dying out. My family history was directly affected by the turmoil in Ireland over the past century, but does that give me more claim to an Irish identity than someone whose family came to North America during one of the famines?

If you try to think of the most Irish thing you could possibly imagine, you might picture Irish dance—made popular by the touring show Riverdance and its sequel Lord of the Dance. The shows are dazzling spectacles of Irish music, Irish step dancing, fiddles, and classic Irish iconography. The dancer and the choreographer at the heart of it all, Michael Flatley, is seen as one of the more famous Irish figures in pop culture. When I was a child, my nan would put an old VHS recording of Lord of the Dance on while she made soda bread for Saint Patrick’s Day, and both she and my mom have told stories of seeing Michael Flatley live.

Michael Flatley is American. He was born in Chicago. The modern Irish dance revival was orchestrated by, for all intents and purposes, the ultimate Plastic Paddy.

(I haven’t broken this news to my nan yet, and I probably never will.)

The ability to pick and choose aspects of identity is not a privilege that is afforded to all, and none of us are able to erase the context of the identity we form or have assigned to us. Understanding the context is paramount in terms of discussing identity, but whether it matters to the individual is entirely personal.

The context matters to me only so much as how I contribute to the context. How I can do better. How I can balance familial identity with the broader realities of the social construction of race and whiteness in North America.

It is, ultimately, a fine, fine balance between who we are and what, within our contexts, we can choose to do.