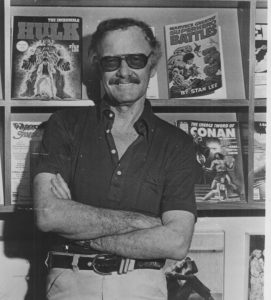

The mind that changed comics

By Brittney MacDonald, Life & Style Editor

With all of the constant cameos and the stories of kind fan-encounters, it becomes easy to forget that before Stan Lee was the Marvel icon we’ve come to know and love, he was a writer who changed an entire genre.

It is true that alongside partners like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Lee managed to forge early incarnations of some of the most legendary superheroes. However, I’m referring more to the way Lee managed to alter the expectations of comic writing. For a long time, I wrote “Comic corner,” a column reviewing various new and old comic books and graphic novels for the Other Press. As a critic, I expected that what I read—whether it was a single issue, omnibus, or stand-alone title—had to be held to the same standards of writing that any book would. This meant that regardless of the overarching plot or theme of the series, each installment had to have enough content to be read independent of the collected work. I also expected that what I read wouldn’t be simple fluff meant for children, and that the characters would be fully developed, three-dimensional beings. Stan Lee is the reason I am able to expect all of this from a comic book.

In the ’60s Lee pioneered the idea that comic characters shouldn’t be simplistic and that superheroes especially needed to be more fleshed out. At the time, comics were filled with carbon copied do-gooders who fought evil because that is what good people do. That was the only motivation given or expected. They also were written to have no flaws and to be morally superior no matter what. Lee, who originally wanted to be a novelist, obviously disliked this approach. Alongside his creative partners, he introduced aspects of grey morality and psychological flaws to the characters they penned.

A good example of this is the Silver Surfer, whom Lee has named as one of his favourite characters he’s worked on. The Silver Surfer first appeared in The Fantastic Four #48 in March of 1966. One of his key traits, and one that has been carried on by Marvel writers even beyond Lee’s direct involvement, is that he is a superhero who struggles with his own pacifism. He often second-guesses himself and is prone to philosophical monologues questioning the nature of humanity, violence, and the “greater good.” This kind of introspection would have been impossible had Lee stuck with the status quo.

With Lee, Ditko, and Kirby, comic book characters were suddenly given entire character arcs, so their personalities could evolve and change. Essentially, Lee and those who worked with him made it possible for their creations to be affected by experiences. In Amazing Fantasy #15, which Lee released with Ditko in 1962, they introduced Spider-Man, who was intentionally written to be relatable. As such, he was flawed in that his initial response to crime and injustice is to not involve himself. However, this famously results in his uncle’s death and he begins a personal quest to make amends by fighting crime. This is the source of the famous quote, “And a lean, silent figure slowly fades into the gathering darkness, aware at last that in this world, with great power there must also come—great responsibility.” However, this was not the case five years later.

In Amazing Spider-Man #50, which was released in 1967, Lee worked on a story arc with writer-artist John Romita Jr. Spider-Man decides to quit, citing that after so many years and all of the personal loss he has suffered, he has already made up for his earlier mistake. However, the absence does not last because Spider-Man finds that after so much time spent righting wrongs, he is now incapable of playing the bystander. This sets the stage for his new flaw—his inability to ignore anything against his personal moral code. Later incarnations of the character saw future Marvel writers running with this. They continued to use Spider-Man’s new established psychology to prompt difficulty with platonic and romantic relationships, even including an arc where his marriage falls apart due to him being a “workaholic.”

Since the characters were now full developed, Lee and his compatriots found that the worlds these characters inhabited needed a similar makeover. Lee was adamant in his belief that comics were not only for children. Therefore, they needed complex storylines, complex characters, and equally complex worlds to round it all out. However, due to the restrictions of the Comics Code Authority (CCA), creators often found it difficult to produce narratives that would entice an older audience. These restrictions varied in scope, but in general they acted as a means of censorship because many vendors refused to sell any comics not approved and granted the CCA seal.

This limitation was such an annoyance that Lee almost quit comics. Originally, The Fantastic Four, which debuted in 1961, was supposed to be his last work. As such, in an attempt to spite the CCA, Lee filled the story with intense amounts of drama. Doing so stymied the CCA and those who gave it power. Despite originally not being endorsed, The Fantastic Four was such a commercial success that it prompted the CCA to make an exception for the series and inspired Lee to stay the course.

Later in his career, during the drug- and disco-crazed days of 1971, Lee snubbed the CCA once more. At the time, the CCA had very stringent rules about only allowing negative portrayals of substance abuse. Despite this, Lee and Romita Jr. put forward The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 . These three single-issue comics featured a narrative in which key character Harry Osborn develops an addiction to unnamed pills. In the story, Osborn eventually suffers an overdose and nearly dies as Spider-Man helplessly looks on. The story tackled a very real-world issue and as a result was a hit among fans and a financial success—even though it never gained the CCA seal of approval.

Lee and his co-creators were also responsible for the idea of an interconnected fictional comic multiverse. This meant that characters, events, and plots could stretch and be interwoven between several different titles simultaneously. This added an extra degree of complexity to the narratives Lee and his fellows created. Thanks to the multiverse, situations and conflicts seemed a lot less insular, which made them feel more impactful. Not only that, but it popularized the concept that not every superhero was made equal. Since all of these characters now existed within the same world, it became apparent that some were stronger or more powerful than others. This was a fairly new and radical idea, since previously superheroes were given a very broad spectrum of power with little to no limitation—think Superman. However, establishing this idea that superheroes may not be all-powerful paved the way for Lee and Kirby to bring about The Fantastic Four #48–50, affectionately nicknamed “The Galactus Trilogy.”

“The Galactus Trilogy” is seen by many comic connoisseurs as being ground-breaking in terms of how it approached villainy. Essentially, Galactus is a cosmic being who functions on the same level as a god. There is literally nothing he can’t do. He sustains himself by absorbing living energy from entire planets—later leaving them devoid of life. To put it very simply, Galactus is Armageddon, or if you’re less biblical, he is an extinction event. After many attempted battles against him, the Fantastic Four are forced to realize that they cannot defeat him and instead have to resort to other tactics. In the end, Galactus strikes a deal with the team and he agrees to spare Earth. The reason this conclusion is so strange in terms of comic narratives is that the villain is never punished. Instead, the superheroes are made to bow to his power and he moves on to destroy some other world.

The moral dilemma this ending suggests to the reader makes it very apparent that children were not the intended audience for it. As such, “The Galactus Trilogy” is still seen as one of the archetypes of villain/hero ultimate conflict plots. This story arc justifies the expectation that not only the characters but also the world in which they exist must be multifaceted. This plot also gave future comic writers the go-ahead to think outside the box in terms of how the desired ending is achieved. The hero doesn’t always have to save the day.

If you didn’t beforehand, then you should know by now why Stan Lee is as revered as he is. He is the creator because of his involvement with creating some of our favourite superheroes. However, more than that, he is someone who wasn’t afraid to ask for more—more complexity, more heroes, more philosophy. Stan Lee was a revolutionary within the comic industry, more than any one person should be. He will be greatly missed.