How media and government fail to provide the answers

By Mercedes Deutscher, News Editor

What would you do if your best friend disappeared without a trace? How would you react if your sister’s body was discovered in a suspected homicide?

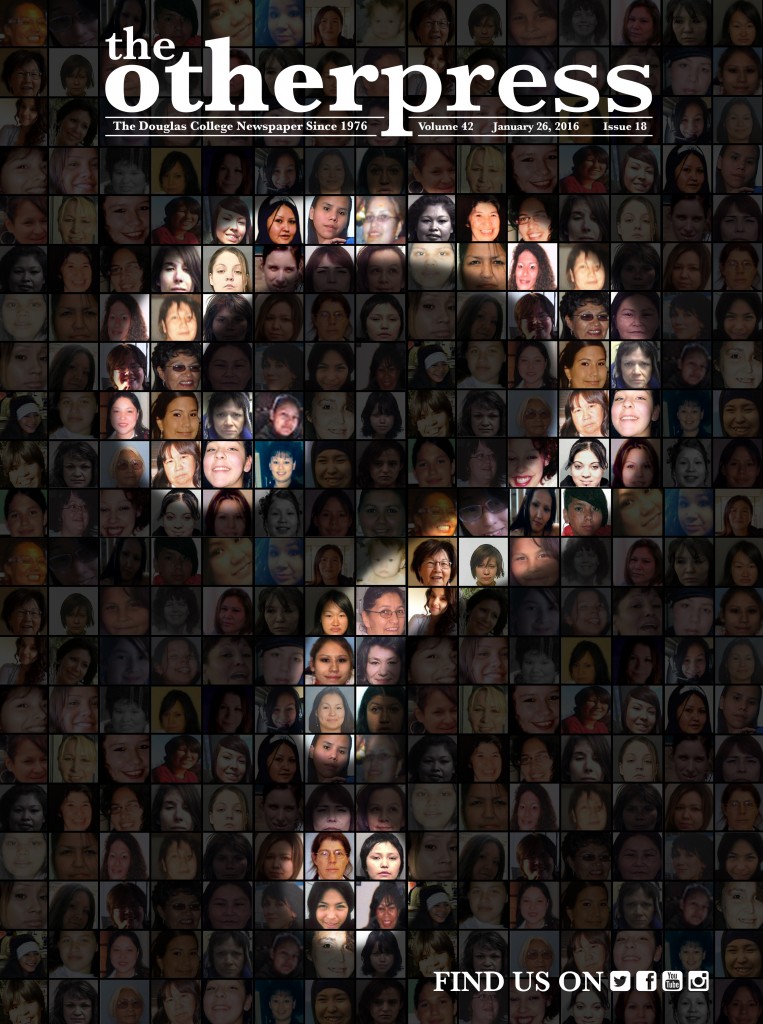

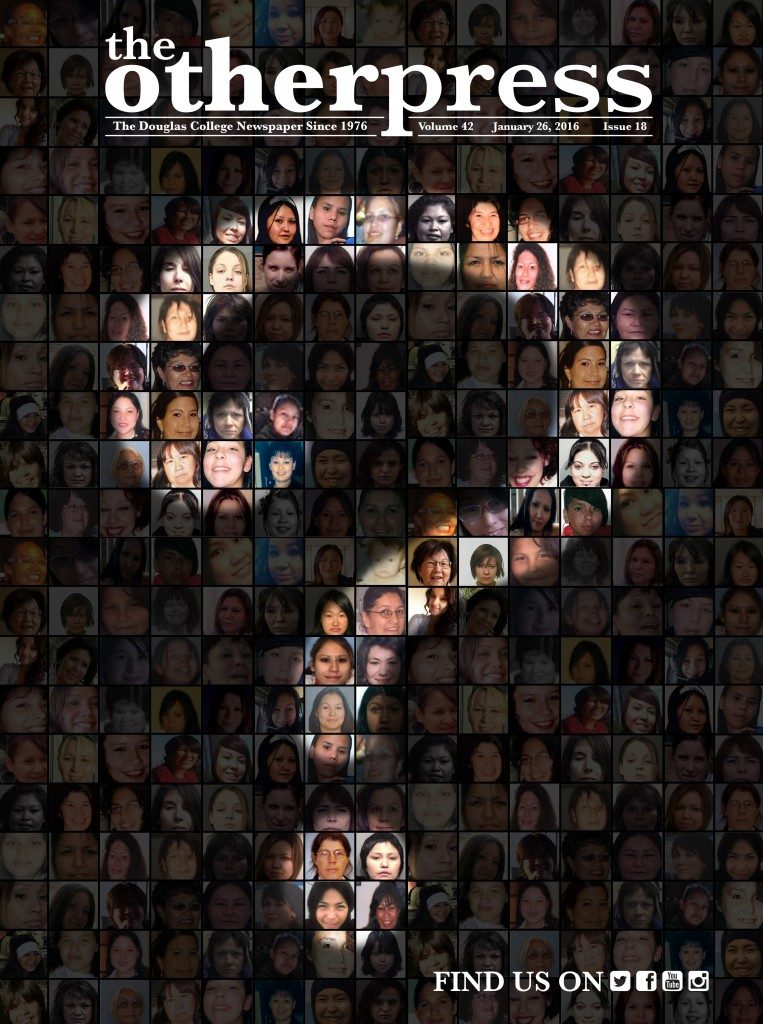

As horrific as it sounds, this is a reality known to thousands of Canadians affected by the loss of 1,181 women who have disappeared or have been murdered since 1980, according to the RCMP’s 2014 report “Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: An Operational Overview.” What do these women all have in common? They belong to Canada’s indigenous population.

It was an issue that was well-debated and highlighted in the recent federal election, but where was the concern prior to that? Seemingly, the Canadian government showed little, and at times no concern for these women until it was criticized by the United Nations Human Rights Committee in mid-August.

“The Committee is concerned that indigenous women and girls are disproportionately affected by life-threatening forms of violence, homicides, and disappearances,” according to the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. “Notably, the Committee is concerned about the State party’s reported failure to provide adequate and effective responses to this issue across the territory of the State party.”

Despite the fact that this horrific phenomenon has been occurring throughout the country for at least 36 years, the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women has only recently come to common public knowledge. In brutal honesty, it is most likely due to how desensitized Canadians have become to violence against Aboriginal women.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) has been tracking the issue for years and fighting for a national inquiry. NWAC released some statistics in 2010 that showed some of the facts and realities of the cases of missing and murdered indigenous women.

In its study of 582 cases of missing and murdered women, 92 per cent involve women under the age of 45. Even young girls are not exempt from the violence, as 17 per cent of these victims were 18 or younger.

This is an issue that has been affecting indigenous women nationwide. British Columbia is the most dangerous place in Canada for these women, accounting for 28 per cent of cases. The western provinces of BC, Alberta, and Saskatchewan account for 54 per cent of cases, while central Canada accounts for another 29 per cent. Atlantic provinces have maintained the safest environment for the women, as only two per cent of cases have occurred there.

Of course, these women were and are so much more than numbers. They all have their own story. An anonymous source shared a tale about a woman she once knew.

Her name was Joyce Hewitt, although she went by Joy.

To the public, little is known about Hewitt, other than her fate. According to a limited CBC profile of her case, Hewitt was found dead on October 19, 1997. Her remains were discovered in Sherwood Park, Alberta.

It was during her time in post-secondary that my source discovered what had happened to Hewitt.

“I went to college some years ago and through Aboriginal studies learned that her name was on a police database stating… I cannot even type it. I am so angry.”

Allegedly, Hewitt sustained a “dangerous lifestyle.”

Many of these women faced struggles in their lives, including drug use, alcoholism, homelessness, and sex work. According to NWAC’s data, approximately 50 per cent of the murdered women were known to or suspected to have some prostitution ties.

What doesn’t seem to be commonly known is that so many of the women that were involved in prostitution were trafficked into it against their will, as was the case with Bridget Perrier.

Perrier, now 39, was trafficked on ships in Lake Superior when she was only 12 years old. She was taken by a sailor and kept on his ship. Once aboard the ship, she recounts the sailor threatening to kill her if she didn’t comply with his demands.

For her safety, Perrier dyed her hair and lightened her skin to pass as non-indigenous, as she recalled that indigenous women were paid minimally and treated poorly.

Perrier made it out alive, a fate that was not awarded to so many other girls. She now advocates for more police patrolling around the lake, where this trafficking is still suspected to occur. Up until recently, these reports were dismissed by the local police as little more than a myth.

“First Nations girls are targeted and my biggest concern is that there are bull’s eyes put on them and no one is doing anything,” Perrier said to CBC.

Why so often do the media, police, and government disregard these cases—or worse, use the circumstances to blame the victim? In my research, I experienced difficulty finding current statistics on the violence against the women, but it was easy for me to find information that painted them as irresponsible women with high-risk lifestyles.

Women, or anyone for that matter, do not deserve to die or to suffer because they are addicts or prostitutes, nor because they belong to a traditionally marginalized population. We need to work to stop the victimization of these women, but we have to overcome sexist and racist preconceptions that some lives are less valuable than others. The police and the public sector need to look at these cases as an example of what we are doing wrong.

What if these women had access to services such as counselling, rehabilitation programs, or safe houses? What if that struggling teenager had better support to finish school? How many of these women could we have saved? How can we prioritize solving the mysteries surrounding these women when they are so often portrayed poorly?

Shortly after the announcement of the federal government’s inquiry, CBC created profiles of 252 missing and murdered women. For many of the cases, this was its first exposure in the media. Yet, even with CBC putting their best effort into portraying the women’s stories, there were many cases where there were no known details of an investigation or a family. It was in these cases where not even a photo of the victim could be found, portraying her as little more than a statistic.

Even within the current Liberal government, which campaigned on a promise of an inquiry, I question how much Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett and her ministry is doing for these women and their families. Mid-November saw a lot of media attention to the announcement of Bennett’s inquiry, which centres on reconciliation and family at its core.

“The more I listen to families, the more I understand they have many instincts and much knowledge about the way we go forward in order to get this right,” Bennett said in a November conference, as reported by CBC.

It is a step in the right direction, but there has been little word on it since. It could be that, over the past two months, investigators have been taking lots of time to speak with families and to put together pieces. But why not even an update?

The complicated mystery of these missing and murdered women has remained unanswered for far too long. So, how do we, as a Canadian society, make up for the injustices faced by over a thousand of our own women? Although we cannot bring back the deceased, we can ease the burden for their loved ones and still save the some of the missing.

We need to listen to the stories told by the victims—like Bridget Perrier— and their families, rather than disregarding them. We need to detect the common themes, like the high occurrences in BC and among sex workers, and question why they exist. We need to recognize the stereotyping that occurs toward the aboriginal community that allows over 1,000 missing and murdered women to be ignored. Then, and only then, can we begin to move forward and heal.