The cyborg future

By Natalie Serafini, Editor-in-Chief

Do you feel that? A vibration in your pocket, and a niggling need to respond. Do you hear that? A ding, trill, whistle, or similarly cacophonous command for attention. Do you sense that? The overwhelming feeling that something has happened in that nebulous, ether-like territory of social media, and the resultant need to refresh, update, and load more.

As technology becomes increasingly entwined with our daily lives, it seems inevitable that it will also become an inseparable appendage to our anatomy. This is true on a literal level, as people seek out magnetic implants, undergo surgeries for pacemakers, or have their bodies increasingly modified in a cyborgian simulation. It is also true on a hauntingly figurative level, as reports show that the brain may identify inanimate objects as being part of the body, extending the “phantom limb” syndrome experienced by amputees—or, at least extending it as far as our always-within-reach cell phones.

It presents some interesting questions about the separation of self and technology. Whether we’ve always had a propensity for appropriating externalities as not only our own but ourselves, or if this has just developed as a result of our growing dependence on innovative technologies. Whether our gradual progression to a cyborgian state is good, bad, or a neutral fact of humanity’s development. What the implications could be for generations that have no memory of an existence sans iPhones, Internet, and Google Glass. And how our perceptions will change as we see a world passing in the periphery, eyes locked on a glossy smartphone.

Before Current Era

If we’re referring to all forms of technology, technically speaking our adulation of innovation dates back further than recorded history, to prehistory. There’s been evidence of stone tools dating back as far as 2.5 million years ago, with fire emerging roughly 500,000 years ago. From there came kilns for pottery, bricks, weaving and spinning, farming equipment, and the notoriously groundbreaking advent of the wheel. Technology throughout centuries has been and will continue to be a necessity for survival, in facilitating farming, defence and protection, travel, artistic expression—the list continues unendingly.

In addition to those survivalist modernizations is the significance of technology in communication. The alphabet itself is a form of technology, presenting the building blocks for words, sentences, and soliloquies. Without some base forms of communication, our lives would be lacking the rich complexity and depth of language, our history would possess gaps through the absence of a recorded history, and relationships would be stunted by an inability to profess our feelings, attitudes, and intentions.

Basically, we’ve been dependent on technology since we realized its significance to not only our existence but the quality of our existence.

Current Era

Our dependence on technology is nothing new, but perhaps the ways in which we’ve melded metal with flesh are. Body modifications are a prime example of how we’ve accepted science fiction into our reality, whether they’re the aesthetic modifications of piercings, the medical modifications of pacemakers and other life-saving technologies, or the futuristic modifications of magnetic implants (wherein a small magnet is implanted, usually into the finger).

The magnetic implant is rather appropriately a trend that’s sprung up in the biohacking movement. Simply put, biohacking merges biology with technology. Put in more detail, BiohackYourself.com describes biohacking as the practice of improving oneself with the least investment for the most reward. Biohacks can take the form of any sort of self-experimentation for self-improvement—including mental health and well-being through sheer thought, meditation, or will-power—but the biohacking movement has been closely associated with the use of technology.

Biohacking isn’t just for the self anymore, either: NewsWeek.com reports that the term has come to describe those “biohackers, teachers, librarians, and artists who have gone rogue,” and who bring scientific breakthroughs to the public sphere in “the era of crowd-sourced science, in which almost anyone can make a new creature.”

Already we’re aware of how prosthetics can aid amputees, pacemakers can help a faltering heart, and dialysis can replace the mechanisms of a kidney albeit in an arduous and inconvenient process. Although they meld metal and flesh, or otherwise improve human functioning through technology, we don’t generally consider these to be characteristic of technorganic lifeforms.

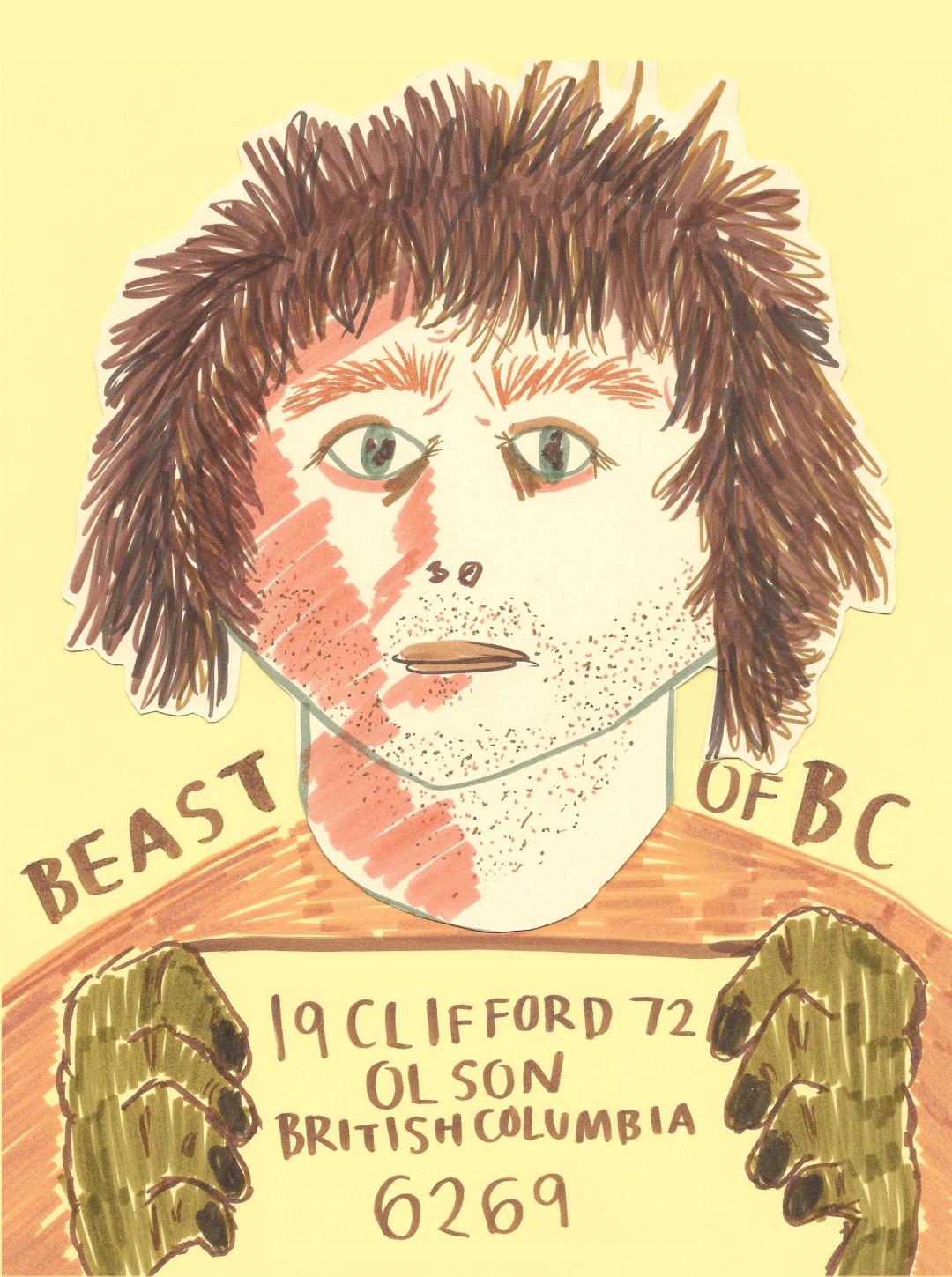

Nevertheless, the cyborg title has become more commonplace, as people develop innovative technologies to improve themselves. Neil Harbisson, for example, is colour-blind and a self-proclaimed cyborg. Harbisson made the news when he had an antenna implanted into his head in order to “hear” colour, addressing the gap in his colourless vision. His partner, Moon Ribas, also identifies as a cyborg and has an antenna attached to her elbow that vibrates when there’s an earthquake.

Technology has also become an intriguing extension of ourselves in less medically facilitated ways. In particular, cell phones have become a lowest common denominator, in the sense that just about everyone has one; age has become increasingly irrelevant, and a lower income generally just means an older phone. The standards of accessibility affix mobiles to us like a bizarre appendage—one that we perpetually check for updates. As Adrian Hon writes, “With our reliance on mobile phones increasing to the point where they’re the first thing we look at in the morning and the last thing at night, would we feel their absence as painfully as a limb’s, creating a ‘phantom mobile’?”

Infinity and Beyond

This progression further and further into technorganic territory is both sinister and tantalizingly embryonic. Sinister, because we don’t know what the consequences might be of meddling with nature in the way that we have been and continue to do; sinister because we may not have the full knowledge of anatomy and humanity—down to the minutest atom—to pursue such experimentation. It’s tantalizingly embryonic though because the potential is immense, and we’ve only just begun to unearth the possibilities. As Steve Mizrach writes in “The Ethics of the Cyborg,” “The computer now offers the human race the opportunity to transcend limitations of intellect, strength, and longevity previously ‘programmed’ into its DNA by eons of evolution.” While we don’t know everything about anatomy and humanity, what if we can’t gain understanding except through the use of these ominous technologies?

Still, the consequences could be substantial, and they are not to be discounted. There’s already significant disparity amongst people, through economic differences, prejudices, and inequity; technological superiority, ingrained into your very being, could conceivably aggravate those differences. Mizrach asks us to imagine a dystopian divide between the “biological haves and have-nots,” with the technologically repurposed removed from the myriad sufferances of the regular old human plebeians. If we venture down the rabbit hole of simulation, innovation, and a marriage of metal and muscle, there is no turning back. We’d better be pretty sure about our collective ability to manage—or to introduce cyborg ethics, as Mizrach advocates.

There’s no telling how far we could go, but that also begs the question of how far we should go. It’s bizarre to think of a world of cyborgs, and it might very well be a dangerous prospect with our propensity for prejudice, lack of knowledge, and lack of foresight. Nonetheless, I don’t see that uncertainty deterring our collective curiosity or drive to improve our societies and ourselves; and I think as long as we remain aware of the possibility for disaster, we’ll curb ourselves where we venture too far. We’ll stumble, we’ll experiment, and we’ll find our way—phantom mobile phones clutched in our magnetically-implanted hands.

With the innovation of petri-grown meat on the horizon, and our own gradually increasing simulation, we are, naturally, not entirely natural and not entirely synthetic. We seemingly exist in tension, with discordant opposites coexisting in something like harmony. It’s a brave, bold new world, with the potential for exponential growth or exponential decline—or perhaps something completely different.