Forty years ago, Olson’s murder spree caused panic in our province

By Brandon Yip, Senior Columnist

“One of the parents told me: ‘For years I thought he was a monster, but now that I’ve seen him and heard him speak, I realize he’s just a pathetic little man.’”

– Neil Hall, former reporter for the Vancouver Sun during the Olson murders

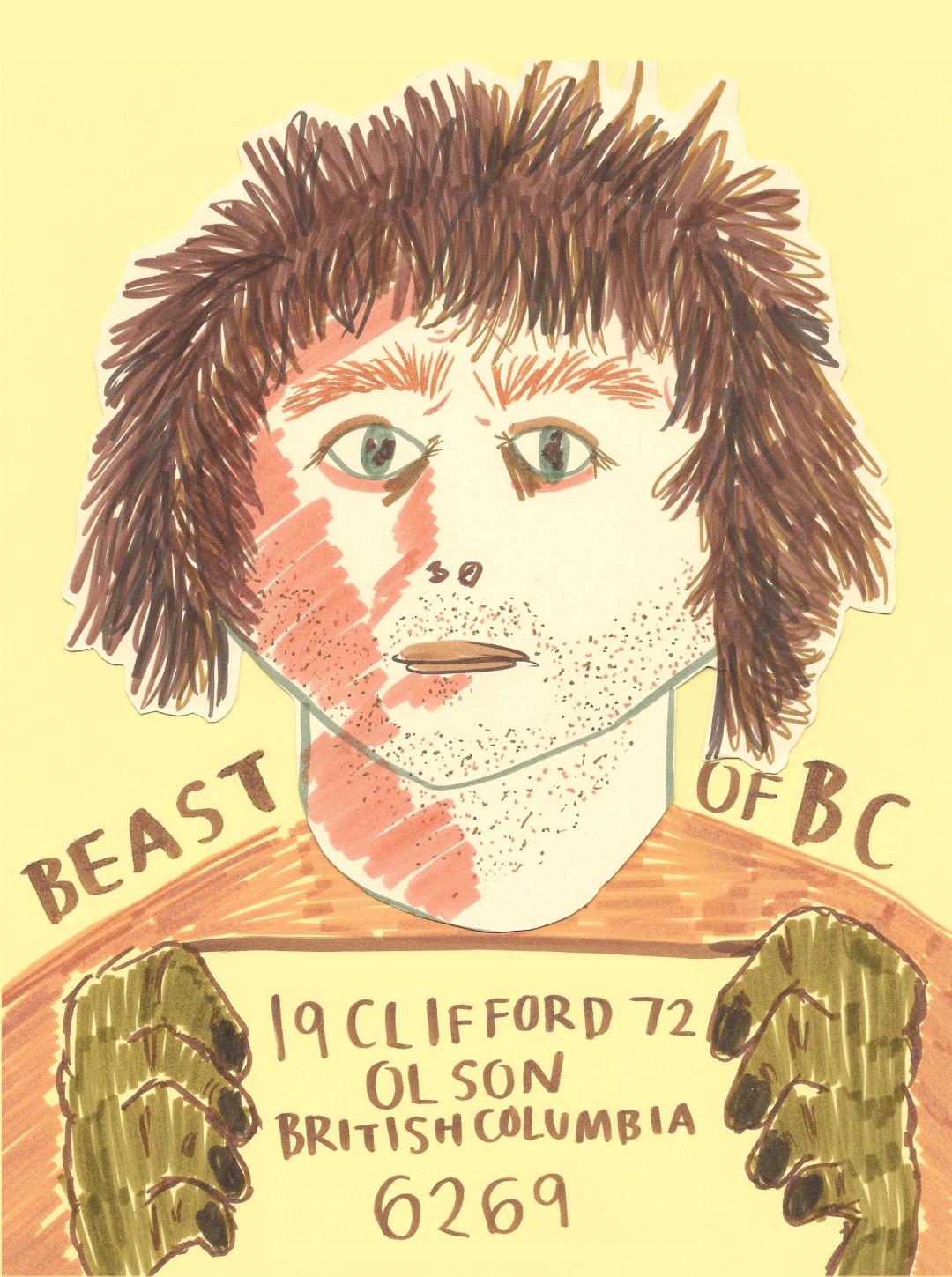

This year marks 40 years from when Canadian serial killer Clifford Olson’s reign of terror ended with his arrest. Olson murdered 11 children (eight girls and three boys) ages ranging from 9 to 18 years.

Olson showed no remorse for his crimes; he took pleasure in taunting the families of his victims. While in prison he even mailed a letter to one family so he could describe in graphic detail how their son died. He also proudly proclaimed himself “The Beast of BC.” When Olson appeared in a Vancouver courtroom to begin his murder trial in January 1982, he carried himself like he was someone of high rank—turning around to smile at the audience. Some of the people sitting in the crowd were the families of his victims. Over the years, with Olson in jail, he continued to make headlines by stirring controversy and causing further agony.

The beginning

According to a Maclean’s article, Olson’s childhood was spent in Richmond. Olson became known as a bully, a con artist, and a thief to his teachers. He was often described as a kid who enjoyed being the centre of attention and was regarded as a promising boxer. Crime was part of his life from the beginning. At age 17 Olson received his first jail sentence and spent nine months in jail for burglary. He eventually escaped and was later recaptured—and this pattern that would reoccur at least six times over the next 20 years. A Globe and Mail piece states he only spent four years in prison during this period and had with over 90 convictions and seven escapes while in custody.

From November 1980 to July 1981, Olson went on a murdering spree while out of prison on mandatory supervision. All of his victims lived in the Lower Mainland in local cities like Burnaby, Coquitlam, Maple Ridge, Surrey, Langley, and New Westminster (with the exception of one who was a German tourist). Olson coerced his victims with concocted stories about work opportunities or other incentives in order to get them into his vehicle. Some victims had been raped and sodomized, some bludgeoned, while others were stabbed, and one had been strangled. He drugged and killed all of them. In August 1981, Olson was arrested on Vancouver Island near Port Alberni under suspicion for attempting to abduct two female hitchhikers in his vehicle. Olson was later taken to Chilliwack for questioning—and two days later he was charged with the murder of Judy Kozma (whose nude body was discovered with multiple stab wounds on July 25). Olson was 41 years old at the time of his arrest and had been working as a carpenter.

Beast behind bars

In January 1982, Olson’s trial would begin—but it only lasted three days. Olson unexpectedly pivoted from pleading not guilty to pleading guilty to 11 counts of first-degree murder; he was sentenced to 11 concurrent life sentences. In a packed courtroom, Mr. Justice H.C. McKay stated to Olson (as the mother of one of the victims sobbed in the background): “I do not have the words to adequately describe the enormity of your crimes, or to describe the heartbreak and anguish you have caused.” He further declared that Olson never be released and “no punishment that a civilized country can impose that would be adequate.” After his trial in February 1982 Olson was sent across the country to be incarcerated in Kingston Penitentiary.

Malcolm Gray, in the previously mentioned Maclean’s article, discussed Olson’s mental state during his trial. Olson was represented at his murder trial by lawyer, Robert Shantz. “As for Olson’s mental condition, Shantz has had five psychiatrists looking at him, and they diagnosed him as a psychopath. Even though he is mentally disturbed, Olson never received psychiatric care while he was in prison and was not legally insane under Section 16 of the Criminal Code. He knew what he was doing when he killed.”

Dr. Tony Marcus, head of Forensic Psychiatry at the University of BC in 1982, was one of the five psychiatrists who assessed Olson. He reported that Olson had “no illusions, delusions, hallucinations.” Marcus also added that Olson typified “the quintessence of the incorrigible, amoral, anti-social psychopath who does indeed know that he has done wrong and does appreciate the nature and quality of the act, though he cannot respond to these acts with the feelings that a normal individual would show.” Also, Marcus stated Olson’s attempt to show remorse for his victims was contrived and “are without depth.” Finally, Marcus summarized Olson, stating “the perpetration of such horror, of such dimension, in such a macabre and horrendous way, is so alien that even people who have met individuals who are called psychopathic or anti-social, cannot bring themselves to believe that there may be individuals of this gross nature. It is too impossible to accept.”

The Other Press interviews a Vancouver Sun reporter from the time of the murders

Former Vancouver Sun reporter, Neal Hall, covered the trial of another local serial killer, Robert Pickton. Hall also covered Clifford Olson’s 1997 “faint hope” parole ineligibility review. “Faint hope” referred to section 745 of the Criminal Code that allowed prisoners convicted of murder and serving a life sentence to apply for a review of their parole release date. Families of Olson’s victims were outraged: “It was controversial because Olson didn’t stand a chance of success,” Hall said in an email interview with the Other Press. “He just wanted attention. But for a lot of the families of his victims, it was the first time that they got to see Olson in person (albeit they were separated in the high-security courtroom in Surrey by a wall of plexiglass). One of the parents told me: ‘For years I thought he was a monster, but now that I’ve seen him and heard him speak, I realize he’s just a pathetic little man.’” Olson’s application would be denied by a judge and the law was later revised to exclude serial killers like Olson.

In March 2010, Olson created more controversy when Global News reported that Olson was receiving more than $1100 per month in Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Supplement payments starting in 2005 when he turned 65. The CBC reported that the Canadian government introduced legislation to end pension payments to some federal prisoners and the act became law at the start of 2011. In November 2010, the CBC reported Olson applied for parole for the third and final time. According to the National Parole Board, it announced its decision to deny Olson parole during a one-hour hearing at Canada’s highest-security institution located in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Quebec. Olson told the parole board, “This is the final time; never again.” Olson declared “and I’m out” as he left the room.

Journalist Peter Worthington had been in periodic contact with Olson since 1989. In a blog published on the Huffington Post the journalist reflected on his association with Olson: “Apart from Bob Shantz, I guess I knew Olson as well as anyone can know a homicidal and narcissistic sociopath. He was a congenital liar and manipulator. You couldn’t believe a word he said. He relished attention, mindful of the Russian proverb: ‘With an audience, even death is attractive.’” A few years earlier in an interview with CBC News in 2006, Worthington stated Olson had never changed: “He knows right from wrong he just doesn’t care. Everything is a kind of learned behaviour. He’s a good con man and he manipulates.” Jon Ferry, who co-authored a book about Olson, stated in an interview with CBC that the Olson case revealed flaws in the way high-profile crime cases were investigated: “Olson mocked the justice system and exploited it and showed its weaknesses. And [it also] showed the poor coordination between the police forces.”

“Something evil was afoot”

Decades after Olson’s crimes, many people still remember the fear Olson put into parents. Corinne (last name withheld) grew up in East Vancouver during Olson’s murder spree in 1981. She recalls her parents driving her to school immediately when children began to go missing. “Clifford Olson took away Vancouver’s innocence in a huge way,” she said in the same 2011 CBC segment. “After Clifford Olson, when kids were [being abducted], bodies were being found […] It just changed the neighbourhood radically. There was a palpable fear in the neighbourhood.”

In addition, Neal Hall remembers the sense of fear and panic when children were going missing in the summer of 1981: “There was a sense of panic at the time. Eleven kids had disappeared by July 1981. It was every parent’s nightmare. Hitchhiking had been common in those days. Parents advised their kids not to hitchhike or accept rides from strangers,” he said in the same email Other Press interview. “But at the time there was still no definitive answer about whether a serial killer was on the loose, so I think the public wasn’t fully aware of one person being responsible for the missing children. Still, there was a sense of dread that something evil was afoot.”

Olson died in prison of cancer in September 2011 at age 71. Perhaps, for many of the families of the victims, there was a sense of justice and satisfaction that Olson was dead. Trudy Court, a sister of one of Olson’s victims, told Global News her reaction to Olson’s death was bittersweet: “These are tears of happiness, because justice is done for the children. Our justice system couldn’t do it for them. But life has. He’s gone now.” As well, Olson’s death will never end the pain and suffering he caused so many families for the last 40 years. Sharon Rosenfeldt says Olson’s death does not bring finality for her family—and told the CBC in an interview: “There is no closure. There is a different way of living but there is no closure, it’s an open wound that goes on and on.”

Remembering Clifford Olson’s victims

1) Christine Weller (13 years old)

2) Colleen Daignault (13 years old)

3) Daryn Johnsrude (16 years old)

4) Sandra Wolfsteiner (16 years old)

5) Ada Court (13 years old)

6) Simon Partington (9 years old)

7) Judy Kozma (14 years old)

8) Raymond King (15 years old)

9) Sigrun Arnd (18 years old)

10) Terri Lyn Carson (15 years old)

11) Louise Chartrand (17 years old)