Controversial decision met with both joy and concern

Controversial decision met with both joy and concern

By Mercedes Deutscher, News Editor

The Vancouver Park Board voted unanimously in favour of banning cetacean captivity at the Vancouver Aquarium on March 9.

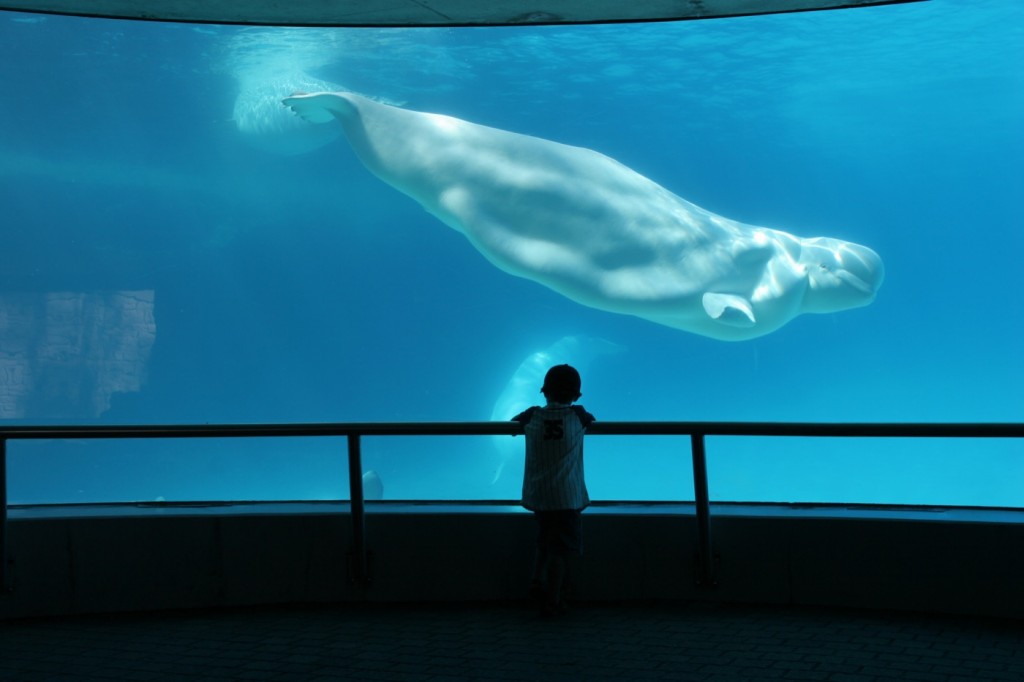

The decision came after the recent deaths of two beluga whales who lived in captivity at the aquarium. Aurora, 30 years old, died on November 25, 2016. She lived in captivity at the aquarium for 16 years. Her calf—Qila, aged 21—also resided at the aquarium, and passed away nine days before her mother.

The decision also comes mere weeks after the aquarium announced that they would be bringing in up to five more belugas, with plans to phase out cetacean displays completely by 2029. However, the park board decision will have precedence.

As a result of the ban, the aquarium may need to find new homes for its three resident cetaceans: Chester, a false killer whale; Helen, a white-sided dolphin; and Daisy, a harbor porpoise. However, the park board may allow the remaining cetaceans to stay.

The decision was cause for celebration by animal rights activists, who have long fought for an end to cetacean captivity.

“It is just time for us not to have cetaceans in captivity,” said Commissioner John Coupar in an interview with CBC. “Times have changed.”

However, other researchers have shown disappointment in the decision.

“A ban on displaying all cetaceans at the Vancouver Aquarium will have a deep impact on the research we do and devastate our marine mammal rescue centre,” said Vancouver Aquarium president and CEO John Nightingale, according to CBC.

Others believe that there should be a middle ground for capturing and displaying these animals.

“It should be injured and rescued animals that are used for display,” Jason Colby, an author interested in the effects of cetaceans in captivity, said to CBC. “Because there’s no more powerful visual impression of that than witnessing an animal that’s suffered because of human violence or human damage to the environment.”

Meanwhile, researcher and activist Peter Hamilton suggested that these animals be housed in a sea pen, likely not available to the public for viewing, which would allow the cetaceans that are unlikely to survive a release more living space, and still allow researchers to observe them.

“They would be in an enriched environment, feeling the ocean currents and different temperatures with a diversity of marine life all around them,” said Hamilton to Metro.

Should the decision continue to remain under scrutiny, the decision may be given to those living in Vancouver. There is a possibility that the question of cetaceans in captivity could be placed to a plebiscite, likely to appear on the ballot for the municipal election in 2018.