Hashtags and callouts have sparked a conversation, but where do we go from here?

By Jacey Gibb, Distribution Manager

“///////”

In mid-October, a post slowly begins popping up in the newsfeeds of people involved with the Vancouver music scene. A woman has compiled a list of abusers—both her own and of others—and posts it on Facebook, encouraging people to message her if they have more names she should add. Attached to the post is an image, and a list of men with varying numbers of /’s next to them. “Each ‘/’ represents a report,” the image reads.

The list has seven names on it, ranging from DJs and promoters to musicians. Within a day, an updated version of the list appears; some of the men have one “/” beside their name; others have six or seven. Between the seven men, there are 22 reports.

Response to the post is swift, and polarizing. The majority of people vocalize their support and thank the woman for posting the list; survivors ask for another slash to be added next to their abuser; people who don’t even know the woman begin re-posting the list in solidarity.

A vocal minority in the comments challenge the woman’s list with the usual deniers’ bingo of responses. In the days that follow, people also mention how one of the accused has been missing since the day before the list was posted.

Shortly, an announcement is made on Facebook that the DJ has passed away; he died a day before the list was released. Only one media outlet directly says the deceased “killed himself,” but many commenters quickly jump to their own conclusions.

“Do you feel good? That you’re a murder? Were all those likes and shares and comments worth your soul little girl?” a friend of the deceased comments on the post. Someone else messages the woman to say thanks for killing their friend.

Shortly after the death is reported, the woman’s Facebook account disappears. Days later, it reappears, but without the callout post.

“////”

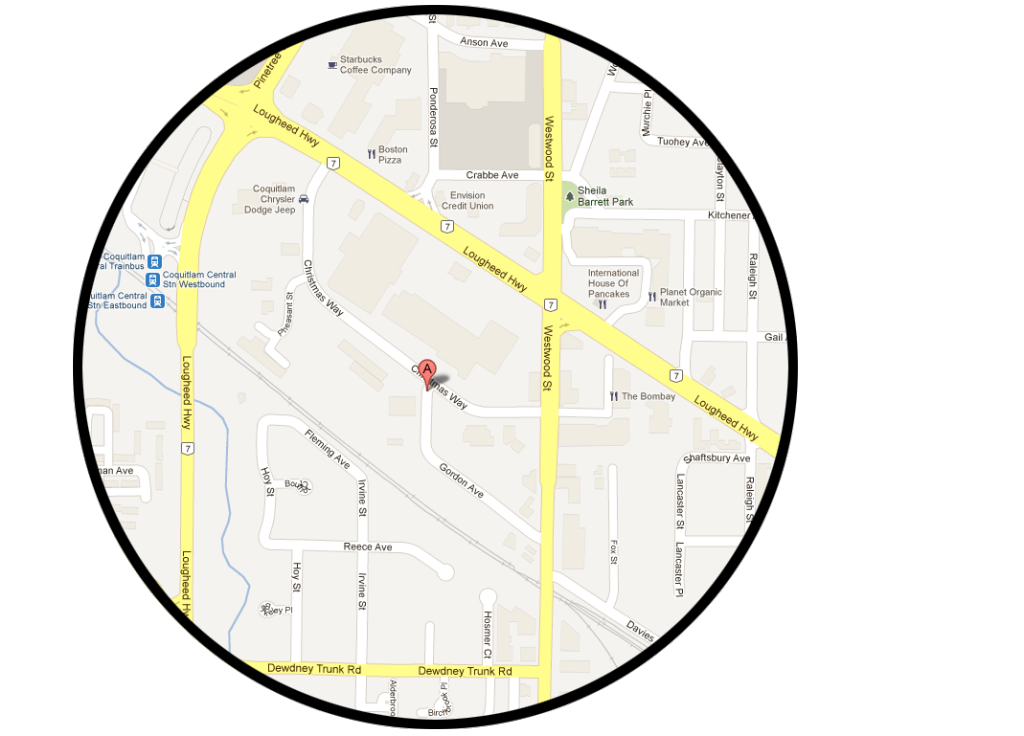

Two weeks after the list appeared on the Internet, I’m sitting in the Vogue Theatre on Granville Street, where Good Night Out Vancouver are presenting a workshop on understanding consent and how to foster a safer nightlife for workers and patrons alike. An offshoot of the Good Night Out campaign started in London, the Vancouver chapter have been advocating for safety and harassment prevention in Vancouver’s nightlife venues—and, understandably, they’ve been busy.

At the start of the workshop, GNO coordinator Stacey Forrester clarifies the intention of the evening: We aren’t there to debate if we live in a rape culture. This isn’t something we’re questioning or trying to poke holes in. Forrester presents it as a fact, and the workshop moves forward without hesitation.

That’s because we live in a society where, traditionally, survivors have been discredited, dismissed, and often silenced.

Data collected by Statistics Canada shows that approximately one in every three women and one in every six men will experience some form of gendered violence in their lifetime, and these are just the incidents survivors are disclosing. Those numbers also don’t take into account other factors, including your ethnicity, if you’re a cis woman or man, or if you have a disability. According to Statistics Canada, if you’re an Indigenous woman living in Canada, and you’re 15 or older, you’re almost three times more likely to experience gendered violence than a non-Indigenous woman.

These statistics also don’t consider that, as a person of a marginalized population, you may not be comfortable reporting incidents to the police.

We’ve all heard about the accusations tearing through Hollywood, but it’s important to realize that gendered violence isn’t something limited to just one industry, or just one city—it’s everywhere.

Emma Cooper is a Vancouver-based comedian, and co-founder of the show, Rape is Real and Everywhere: A Comedy Show, where survivors tell jokes about their assaults. To Cooper, the media spotlight on gendered violence is far from a revelation.

“I was being interviewed and someone asked, ‘Are you surprised by the Harvey Weinstein thing?’ No! There’s a convenient, horrible sexual assault allegation in the news every time we do the show and people always say, ‘Oh, it’s timed up with your show!’ and it’s like, no, this is just everywhere.”

The list I mentioned earlier about Vancouver predators focused on the music scene, but the issue of gendered assault extends far beyond that community. After a prominent local comedian reposted the list, I read a comment that said, “I wonder when the comedy version of this list will be posted.”

In Cooper’s experience, gendered violence hasn’t been a focal point in the comedy scene until recently.

“There’s a scarcity mentality about the lack of spaces to do comedy and a lack of stage time, things like that,” Cooper told the Other Press in an interview. “There are a lot of people who want to do these things, so you already have a competitive situation set up, and if you compound power structures and people following their dreams, you’ve got a recipe for a culture that can have abusers in it.

“There are cases where people have abused their much-less power within the Vancouver comedy scene, and used it to hurt people.”

“/”

A vocal proponent of accountability in the Vancouver arts scene is Brit Bachmann, a visual artist and the Editor-in-Chief of Discorder Magazine. Over the last two years, she’s published several articles exploring gendered assault callouts, accountability, and consent in the local music scene. When the list calling out predators was posted online, she was as confused as I was that some people were quick to dismiss this as a Vancouver-only issue.

“I think people are just really good at compartmentalizing and disassociating, and also trying to define and confine problems,” said Bachmann in our interview. “For instance, a lot of the callouts in Vancouver, it comes very ironically almost six months after a huge wave of callouts in Montreal, and yet, there were comments like, ‘Only this could happen in Vancouver,’ or ‘Vancouver men are bad, Vancouver men are the worst in the country.’ These weird generalized statements … they really dismiss survivor experiences across the country.

“It’s a bit of a control thing, and it’s really based out of fear. Nobody wants to really do the work, looking into their own circles, and analyzing the people around them. Nobody wants to admit that maybe an old boyfriend of theirs didn’t respect consent, nobody wants to look at their coworkers and ask if they’re predators.”

The callouts Bachmann refers to occurred when Montreal-based DJ Catherine Colas took to Facebook, calling someone out after “more than eight women” had confided in Colas that he’d abused them. Reaction to Colas’ post was eerily similar to what happened after the Vancouver list was posted.

Bachmann continues: “When Catherine came forward and was able to share the stories from survivors, it took an incredible amount of strength on her part, and suddenly she was attacked from a lot of different angles, and it was a situation of social martyrdom. I would guess that [the woman who made Vancouver’s list] is probably going through a very similar experience right now, having been contacted and having had to read through and acknowledge a lot of really tough stories from survivors in the local scene.

“It shouldn’t be this way, but it appears as though it takes a certain amount of martyrdom on the part of a strong survivor to get these waves of callouts happening.”

Social media has granted survivors an immense degree of agency, where they are able to publicly call out their abuser(s), but there can also be serious legal repercussions from it.

The legal definition of defamation is “a statement that injures a third party’s reputation,” and can include both written and spoken statements. Calling someone out as a predator can open survivors up to defamation lawsuits, which was even documented in a 2014 xoJane article titled “It happened to me: My rapist sued me for defamation.”

“Legally, calling someone out isn’t the best thing to do, if you fear being dragged into the courts for a defamation suit or something,” said Bachmann. “In terms of defamation, it’s plaintiff-friendly, which is so bizarre. It’s not an innocent-until-proven-guilty situation, it’s assumed-guilt unless you can prove otherwise. It’s assumed malice.

“It makes it very difficult for survivors to come forward, and then for accountability, it makes it almost impossible.”

“/”

There are also risks involved for journalists who want to report on callouts and other gendered violence allegations.

Last year, The Vancouver Sun published an article claiming that Simon Fraser University (SFU) had failed to follow up on complaints made by three women against a male student they say assaulted them. SFU’s student newspaper, The Peak, then pursued the story.

Natalie Serafini, The Peak’s copy editor when the story first broke, said that when the women complained, SFU simply moved the alleged to another residence, and didn’t warn students at the new residence.

“Maybe they couldn’t legally do that, but it seemed like a disregard for people’s safety, to not take these allegations seriously,” said Serafini.

Serafini also described how some of the women who initially came forward to the Vancouver Sun later gave interviews to The Peak, only to reach out again and say they’d been advised not to talk to the press, even if it was anonymous.

“It felt like these survivors were being silenced, where the university hadn’t listened to them to begin with. One woman had to see this guy in her classes, had to run into him in the food hall.”

Reporters at The Peak knew the name of the accused, and Serafini remembered doing a lot of research on whether they could “make a non-anonymizing reference” to him, but ultimately, they didn’t. Even using quotes from someone else can still be considered libel for a publication running the story.

In the months that followed, The Peak reported on the university’s changing policies, and how they would address their lack of a sexual assault policy. Serafini said it was a positive thing to focus on how individuals would be held accountable, and how the university was going to keep its students safe.

“I get so frustrated when people report on sexual assault, and talk about how the person who did it was ‘such a great guy’ and ‘has such a great future,’” said Serafini. “The Stanford rapist is such a prime example of that, and there were so many articles talking about how he’s a future star swimmer. Sexual assault is a really difficult thing to report on, but it’s one of the most important topics to be conscientious of.”

Six months after the story broke, SFU released a first draft of their sexual violence policy, which includes training programs and creating a new resource office that offers services and support for survivors.

“/”

“Now what?”

It’s a pairing of words that appears over and over again in my interview transcripts, appearing in a slideshow at the Good Night Out Vancouver workshop.

In spite of the legal risks and potential for martyrdom, survivors are coming forward to share their stories and—in some cases—call out their abusers. But even when someone’s been called out, what happens next? As a community, where do we go from here?

Bachmann cites a lack of resources available as to why society stumbles when it comes to the post-callout.

“What a lot of these lists fail to do, and what local organizations have been unable to do yet, is to step up and offer resources. A lot of the discussions that I had with people was like, ‘Okay, all of this happened, all of these people have been called out. Now what?’ For the people who have made these callouts, for survivors, if they want help or somebody to talk to about this, where do they go?

“Or for people who’ve been called out, if they actually want to commit to a process of accountability, how do they go about that? Suddenly, there was this huge vacuum and … no organization really stepped up to help out with the ‘What do we do now?’ question.”

Oftentimes, a knee-jerk solution for when someone’s been called out is to ostracize them. Advocates and survivors band together to push a predator out from whatever scene they belong to, and that’s it—the predator is no longer a threat to the community. However, this doesn’t correct the behaviour, and it can lead to the individual making their way into another community where people may not know about the predatory behaviour.

Between culture scenes, Bachmann said, there’s no real network for information on predators to travel on.

“Whereas this little network of quiet gossip and whispers has worked in certain ways, it’s really not worked in terms of actually protecting people in different art scenes. You don’t want [alleged predators] to suddenly become anonymous in another place, because that’s just going to perpetuate the problem.”

According to Bachmann, some groups that have been successful in rehabilitating predators are anarchist scenes, particularly in Quebec. Rehabilitation starts with the predator being called out or admitting their behaviour, and then the community works together to have difficult discussions, with the common goal to have the predator being allowed to exist within the community again. This can be difficult for survivors, Bachmann explains, but the anarchist views of social justice over legal processing have been effective in enforcing accountability—something that our current justice system fails at.

But if you’re part of the majority and not part of an anarchist group residing in Quebec, you may look to organizations and methods a little closer to home.

“//”

Good Night Out Vancouver is just one of the organizations working to promote consent and help shift Vancouver’s nightlife to a more consent-based, safe one. Cooper also notes Consent Crew as another organization that does workshops based on consent, but Cooper is also aware of how strained these groups’ resources might be because of their nonprofit/grassroots basis.

When organizations and other collectives are already working at capacity, the responsibility falls on us as individuals to lead by example, and also to be diligent in calling out inappropriate everyday behaviour. Cooper says they are particularly looking at what male members of the population are going to do now, and hopes they take the lead by talking to other men:

“I’m interested in actions, above all else, coming from people. There are people already doing this kind of work, making an effort to book women and change culture, and it’s not a glamorous thing. You don’t get cookies for it; it’s just a thing you do because you believe other humans are also human people. It’s so basic that you don’t get to brag about it, even though it’s a shit ton of work.

“Most people are still in the ‘get off of the couch’ phase in realizing this is a thing, and learning about it and doing some small action that are first steps. We’ll worry about men burning out in the fight for gender equality later, because I don’t think we’re there yet.”

“//////”

Last week, Sarah Silverman broke her silence about the now-confirmed reports against fellow comedian Louis C.K, a man who was recently outed for masturbating in front of multiple women without their consent.

In the opening monologue of her show, Silverman condemned what C.K. did and emphasized that attention needs to be on the survivors right now, but Silverman also let people know that she’s still processing things. “I just keep asking myself, ‘Can you love someone who did bad things? Can you still love them?’”

After the DJ’s death last month, a woman made a Facebook post about her relationship with him. About their inside jokes, and banter, and how one night after a party, they were making out, and she told him to stop, and he didn’t listen.

“[He] was my friend, and he raped me, and he committed suicide. All of these things are true, all at the same time, and I don’t really know how to deal with any of them.

“You can hate the shitty actions someone committed, and still be really fucking sad that they’re dead. On the other hand, it does not mean that the people he hurt should now be quiet.”

We’re living in a rape culture, unequivocally. Now what are you going to do to help correct that?